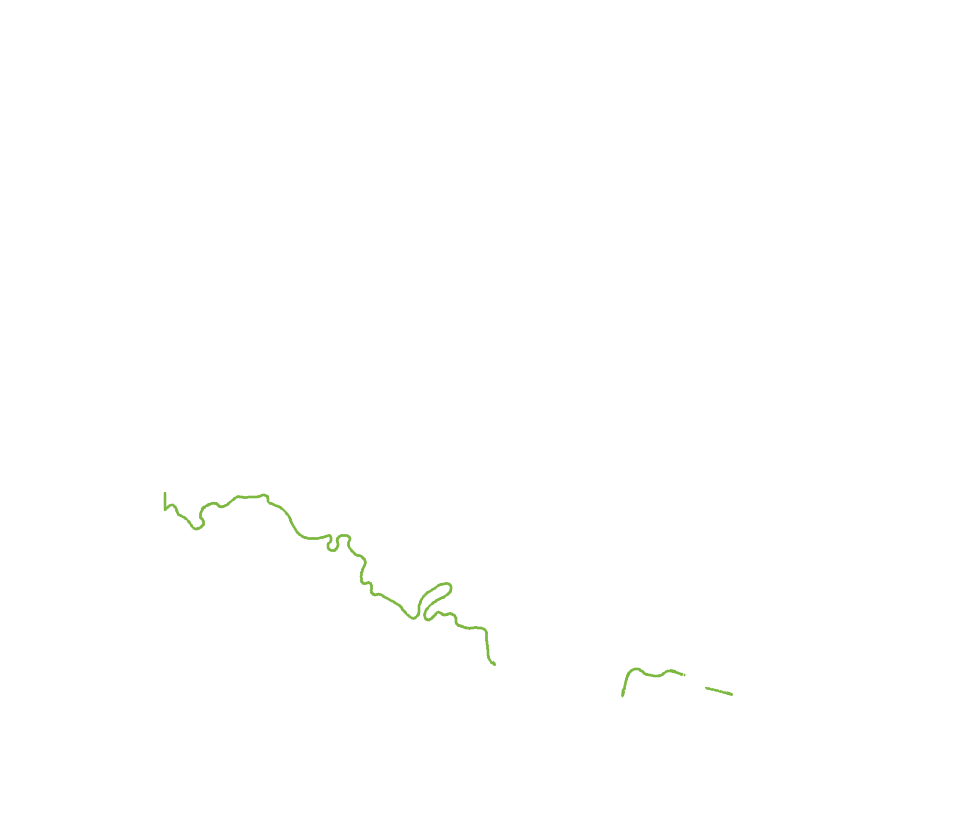

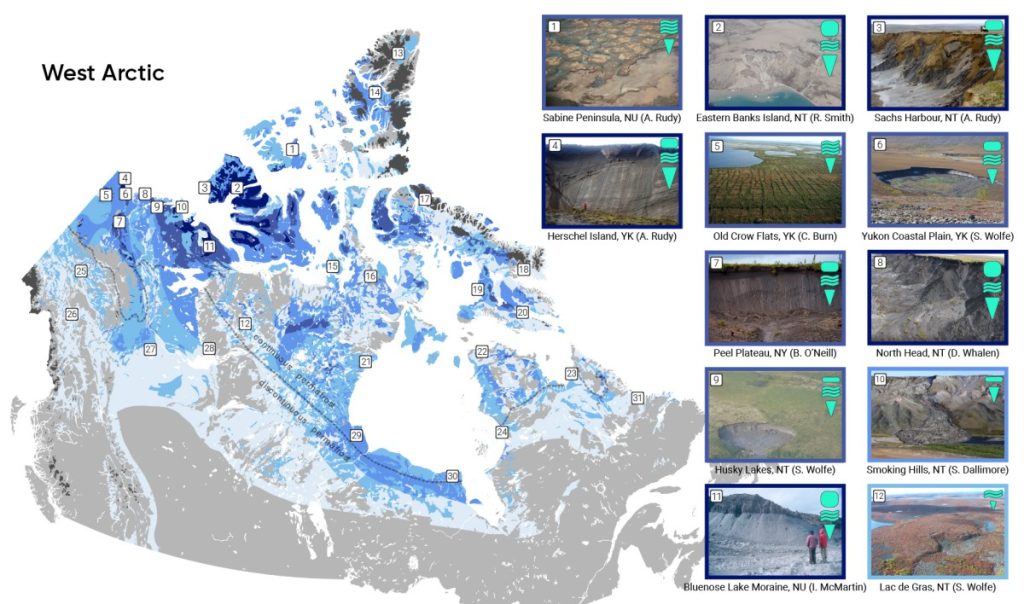

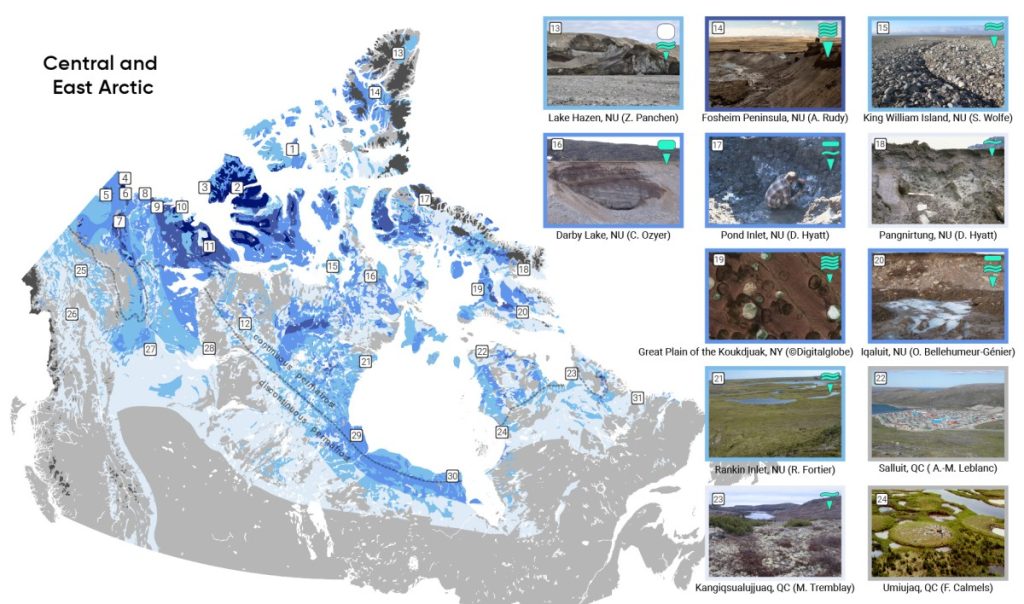

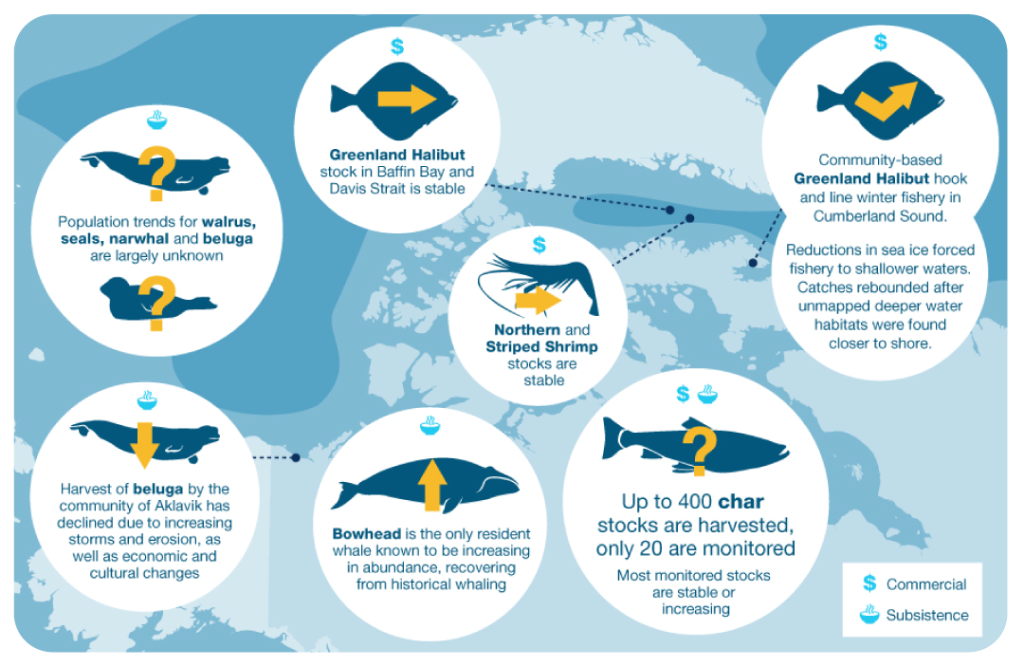

In a region where much of society is deeply tied to the natural environment, changes to the land have the potential to deeply impact the people who live there and who depend upon the land. Many Northerners report that their livelihoods, culture, relationships with the land, and mental health and well-being are being impacted by environmental changes (Kuzyk and Candlish, 2019; Meredith et al., 2019; Bell and Brown, 2018; Stern and Gaden, 2015; Berry et al., 2014), including climate change (see Figure 6.1). While the adaptive capacity of Northerners, especially Indigenous Northerners, has allowed them to be resilient to change for generations (Pfeifer, 2020), the pace of change to which we must adapt has accelerated and is outpacing existing adaptive capacity (Ford et al., 2014).

Canada’s status as an Arctic nation elevates the importance of understanding climate change impacts and adaptation. In its report identifying the top climate risks facing Canada, the Council of Canadian Academies identified climate risks to northern communities as being among the top risks for the country (Council of Canadian Academies, 2019). Meanwhile, the development of the Arctic and Northern Policy Framework demonstrates Canada’s emphasis on the North as an area of policy focus (Crown Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada, 2019).

In addition to climate change, the impacts of colonialism and power differentials in Canadian governance and society affect the capacity of Northerners to adapt to change (Council of Canadian Academies, 2019). Indigenous and non-Indigenous Northerners are working within both historical and contemporary treaties, as well as outside of treaties, to overcome this history and to build community resilience. Efforts to support reconciliation guide the decision making of many northern academic institutions and governments (e.g., Wong et al., 2020). In many cases, hunting programs for youth, on-the-land camps, community-centered infrastructure projects and other measures move northern societies towards reconciliation. These measures also improve relationships between community members and strengthen connection to culture, thereby building climate resilience, but such outcomes are rarely direct goals of the activities implemented.

The lived experience of Northerners and the knowledge held over generations as a result of that lived experience, including Indigenous Knowledge and local knowledge, feature prominently in this chapter and are the basis upon which adaptive capacity is built (see Box 6.1). While there is regional nuance in the messages conveyed in Box 6.1, the sentiments expressed are common throughout the North. This chapter has attempted to include a diverse range of knowledge, while recognizing that further work in this regard is a necessity, and acknowledging that the scientific framing of this report is not entirely compatible with the holistic and applied intentions expressed below.

The history of Indigenous-northern settler relations is a critical factor in understanding adaptive capacity in the North, and does not follow a simple timeline. In the Eastern Arctic, contact between Inuit and settlers goes back to the 1500s (Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami, 2004). Even before oppressive policies were introduced, settlers introduced viruses, at times intentionally, and overharvested key species. These actions ravaged many Indigenous populations in this early contact period (Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada, 2015a; Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami, 2004). By contrast, contact between Yukon First Nations and settler populations happened much later, after oppressive policies and the Indian Act were entrenched elsewhere in early-Confederation Canada. Throughout the North, Christian religious bodies and the Northwest Mounted Police (later the Royal Canadian Mounted Police) played a prominent role in deploying and implementing policies with the explicit intention of eradicating traditional practices and assimilating Indigenous people into “Western” ways (Coates, 2020).

Northern Indigenous voices were almost entirely absent from any policy development until well into the 1970s (Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada, 2015a; 2015b). Instrumental work accomplished during this time period included the James Bay and Northern Quebec Agreement (James Bay Northern Quebec Agreement, 1975), Together Today for Our Children Tomorrow (Yukon Native Brotherhood, 1973), The Dene Declaration (Indian Brotherhood of Northwest Territories, 1975) and the Mackenzie Valley Pipeline Inquiry (Berger, 1976). Since this time, Indigenous populations have been able to begin influencing the policies that had been so detrimental to their People, but this still required Indigenous leaders to largely adopt Western governance approaches. Decades also elapsed before the practice of taking Indigenous people from their homes to attend residential schools was ended in 1996 (Reimer et al., 2010). The first Indigenous Self Governments began to form in the early 1990s (Government of Canada, 1995), but they are not universal among northern Indigenous populations today.

It cannot be understated how deeply past and present-day settler policies have harmed Indigenous Northerners (Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada, 2015a; 2015b). This reality is present in every conversation, regardless of the specific subject matter. As such, it is exceedingly difficult to situate how climate change impacts and adaptation actions relate to other issues and priorities. Nonetheless, climate change is clearly a priority. Changes already observed are alarming to both Indigenous and non-Indigenous Northerners, and the projected pace and magnitude of anticipated change pose daunting challenges for all of us. Indigenous Knowledge approaches clearly demonstrate that strictly applying a reductionist “Western science” worldview is unlikely to lead to lasting solutions being adopted by northern communities (e.g., Council of Yukon First Nations and Assembly of First Nations, 2019; Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami, 2019a). Applying Indigenous worldviews allows us to move beyond linear “cause-and-effect” thinking towards more holistic approaches to building community resilience. This is the northern reality.

Within the context described above, this chapter was developed by a northern organization, featuring contributions made primarily by northern authors across Canada. This approach provides those living and working in the North with the opportunity to identify and write about climate change impacts and adaptation as they are being perceived, lived, studied and experienced in northern Canada. Contributing authors brought a range of knowledge types and areas of expertise, and have experience in the diverse environments in which we live, and the issues with which we live.

Like other chapters in this report, the Northern Canada chapter uses a “Key Messages” approach. The development of the key messages and the identification of the contributing authors and case stories featured in the chapter were guided by an advisory committee through an iterative, consensus-based approach. The advisory committee was made up of Northerners from across the Territorial North, Inuit Nunangat and northern Manitoba. Like our contributing authors, this chapter’s advisors are diverse in their expertise and lived experience, and they worked together to identify issues relevant across our northern home. The broad, engaged approach used to develop this chapter reflects the existing collaborative spirit that is required in order to understand and respond to the impacts of climate change in Canada’s North. The advisory committee met five times―four times virtually, and once in person―to create a long list of topic areas, and then to refine this to a manageable list of draft key messages. This was followed by an effort to recruit authors (ideally who live in the North, and are able to incorporate Indigenous perspectives into their writing). The Coordinating Lead Author and supporting team at Yukon University edited and revised the content, with further contributions from the authors, in order to complete this chapter. The result is a chapter that does not cover all northern climate change adaptation topics, but rather attempts to capture what our advisors consider, based on their experience and expert opinion, to be high priorities for the North.

The key messages in this chapter range from biophysical impacts—including novel disturbances and accelerated rates of change—to impacts on people and culture, through an exploration of holistic health and wellness, public health and safety, and capacity and innovation. These key messages are intended to illustrate the connection between northern society and cultures, and changes to northern landscapes. The complexity of types and degrees of connection to the land and sea, cascading impacts, and appropriate adaptation responses increase with each key message. Rather than attempt to provide an exhaustive list of impacts and adaptations associated with the key messages presented here, we have used examples and case stories to illustrate the central themes of each key message.