Key Messages

Vulnerability factors increase health risks associated with climate change

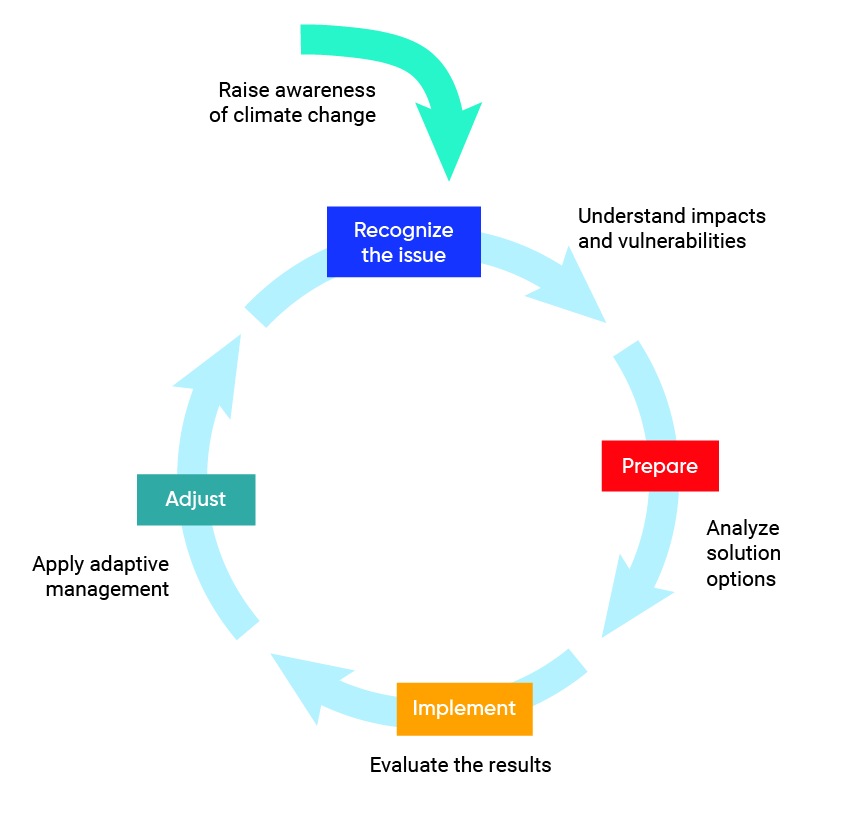

Physical and mental constraints, material and social deprivation, and lack of risk awareness are individual and social factors that can increase climate-change-induced health risks for individuals. In Quebec, to reduce the impact of these factors, interventions aimed at strengthening adaptive capacity and resilience of communities are being implemented for certain hazards such as heat waves and extreme weather events, which are expected to increase in frequency and severity.

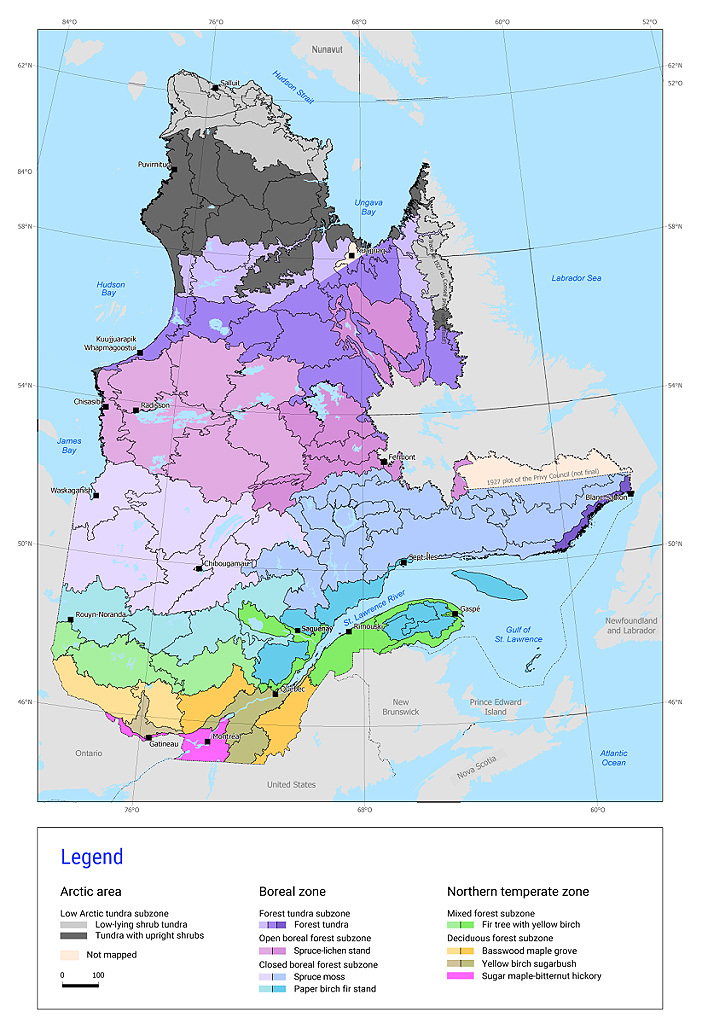

Climate change poses significant risks to Indigenous Peoples and their environment

Throughout the province, and particularly in the North, climate change is threatening the land and the associated living heritage, along with Indigenous Peoples’ connections with them. In this context, the sustainability of traditional subsistence practices, the transmission of Indigenous knowledge, the vitality of cultures and languages, and the spiritual well-being of the communities are at risk. By harnessing their resilience and adaptive capacity, Quebec’s Indigenous communities are proactively planning and designing adaptation measures that consider their current needs and the needs of future generations.

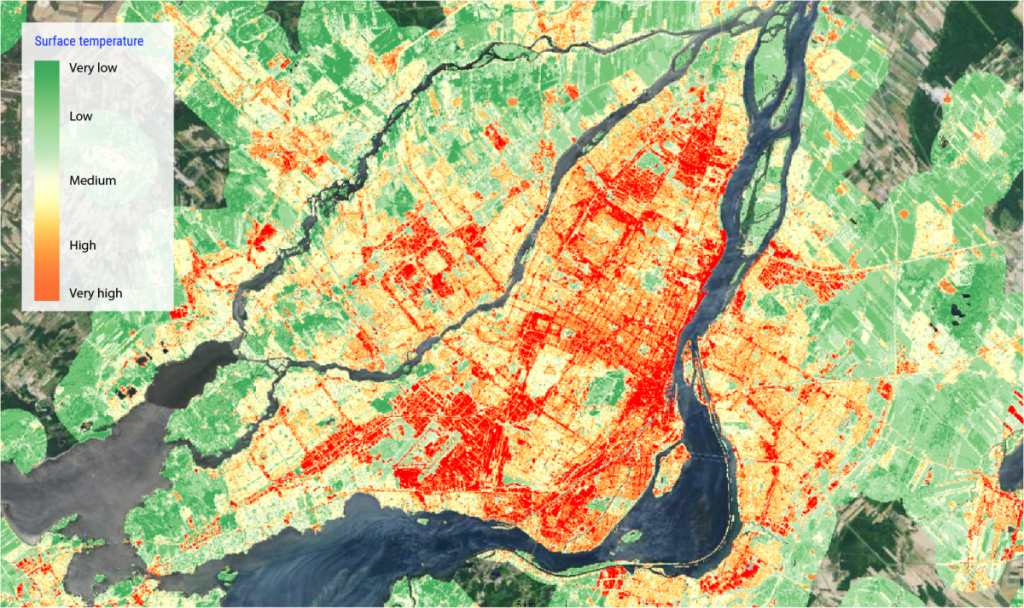

Urban environments are facing increasing climate hazards

Urban areas are grappling with significant health, public safety and environmental degradation issues that will worsen in the coming decades due to climate change. In Quebec, cities are home to most of the population and are faced with growing problems such as heat islands and stormwater management. A growing number of municipalities are developing adaptation plans and strategies to better cope with climate hazards.

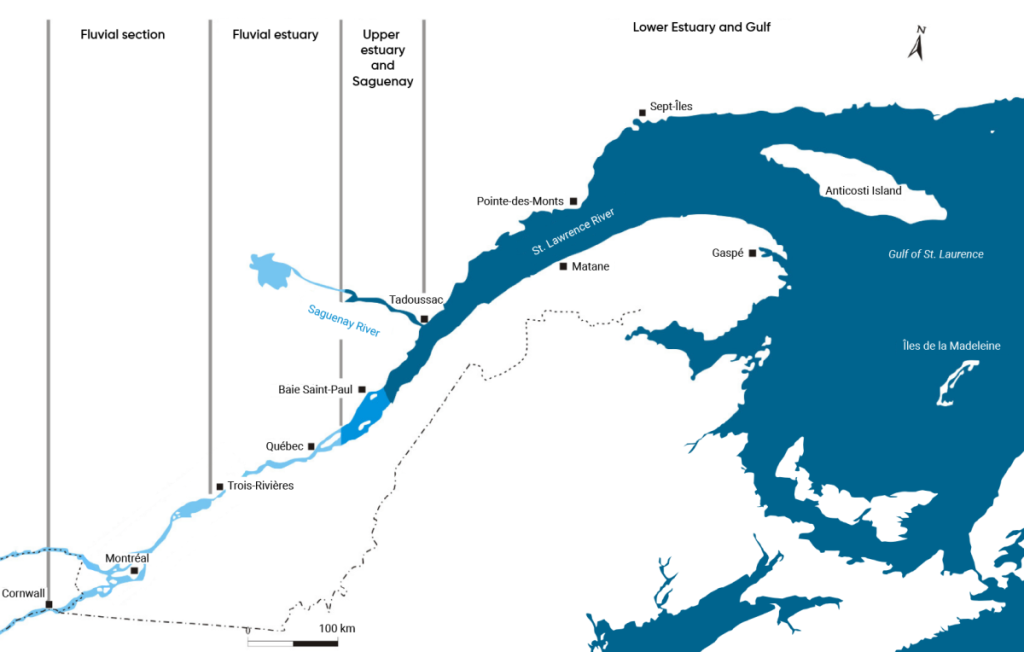

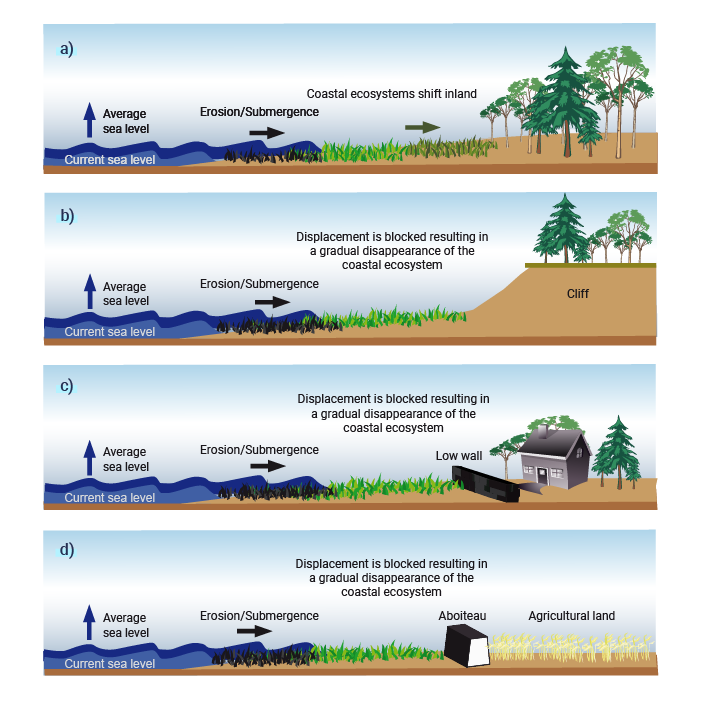

Coastal areas of eastern Quebec are under increasing threat

The coastal areas of eastern Quebec face significant coastal erosion and flooding issues. These problems are exacerbated by the reduction in ice cover that amplifies the impact of storms. In view of the severity of the cumulative impacts on coastal environments, coastal populations in Quebec are making changes to their land development practices to adapt to climate change.

Climate change impacts on water regimes, availability and quality

Quebec’s lakes and rivers, including the St. Lawrence River, will be affected by climate change, which will modify water levels, flood risks, and water availability and quality. In response to potential changes in water regimes, Quebec is implementing adaptation measures, such as updating flood zone mapping, creating a flood forecasting system and protecting wetlands.

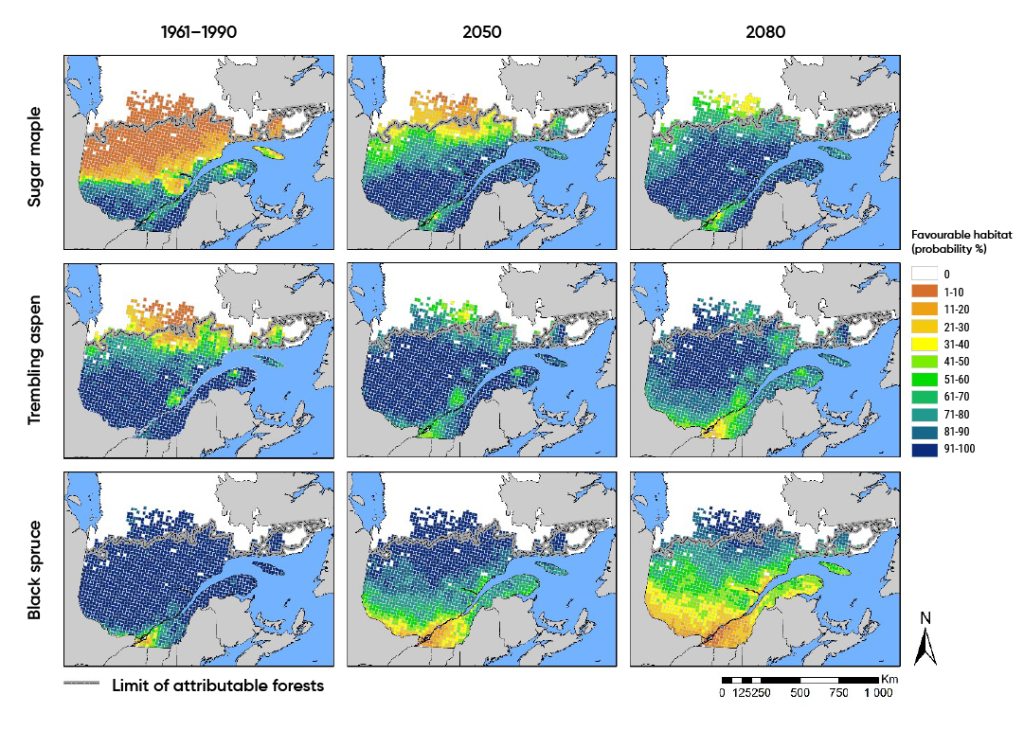

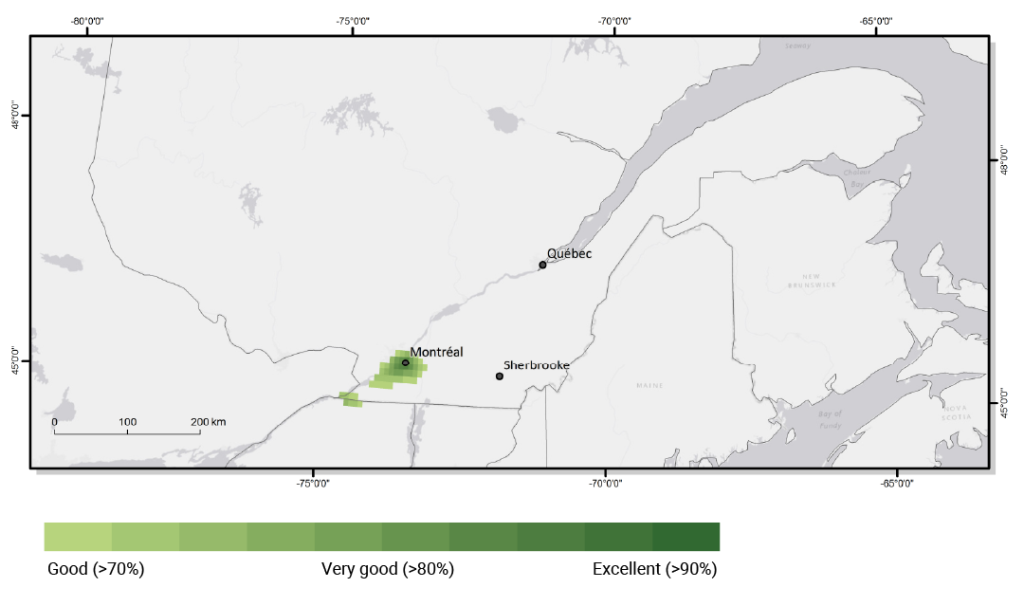

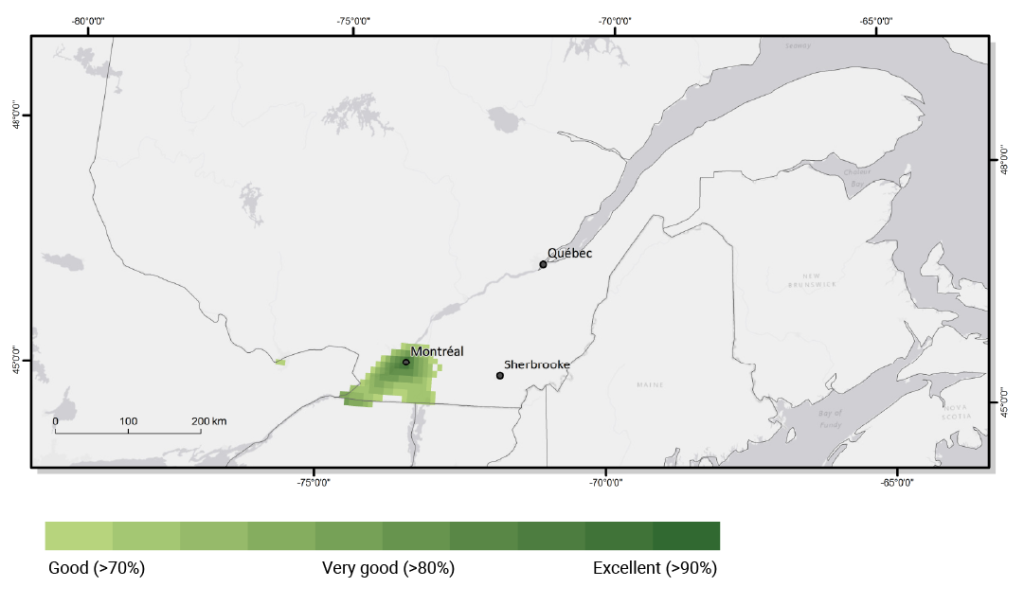

Ecosystem services play an important role in adaptation

Quebec’s population relies on services provided by ecosystems to adapt to climate change. However, Quebec’s ecosystems are themselves impacted by climate change. Several methodologies and tools for monitoring biodiversity have been developed to support decision-making in order to improve the conservation of ecosystems and maintain the ecological services they provide.

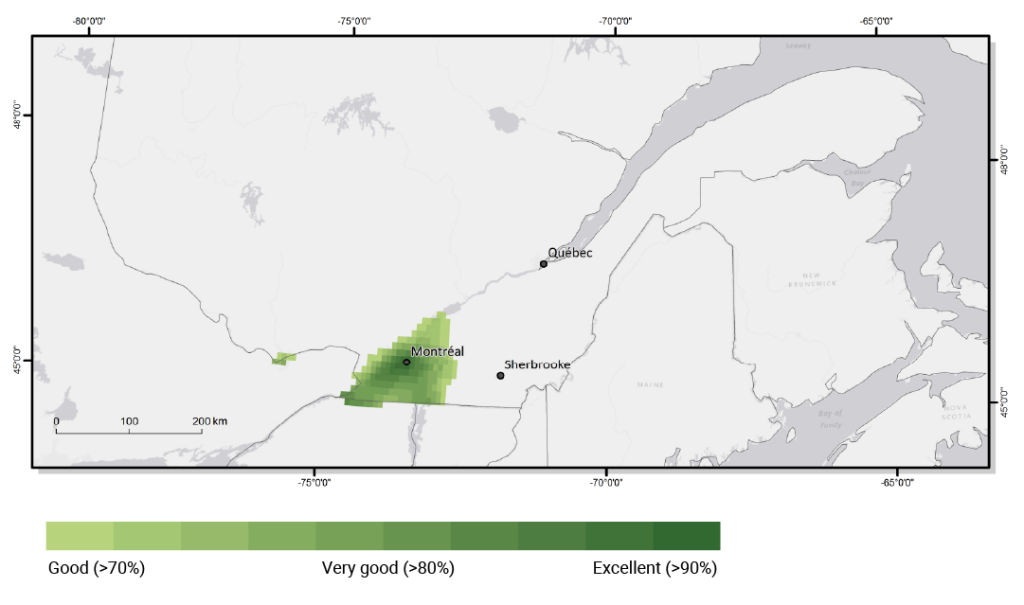

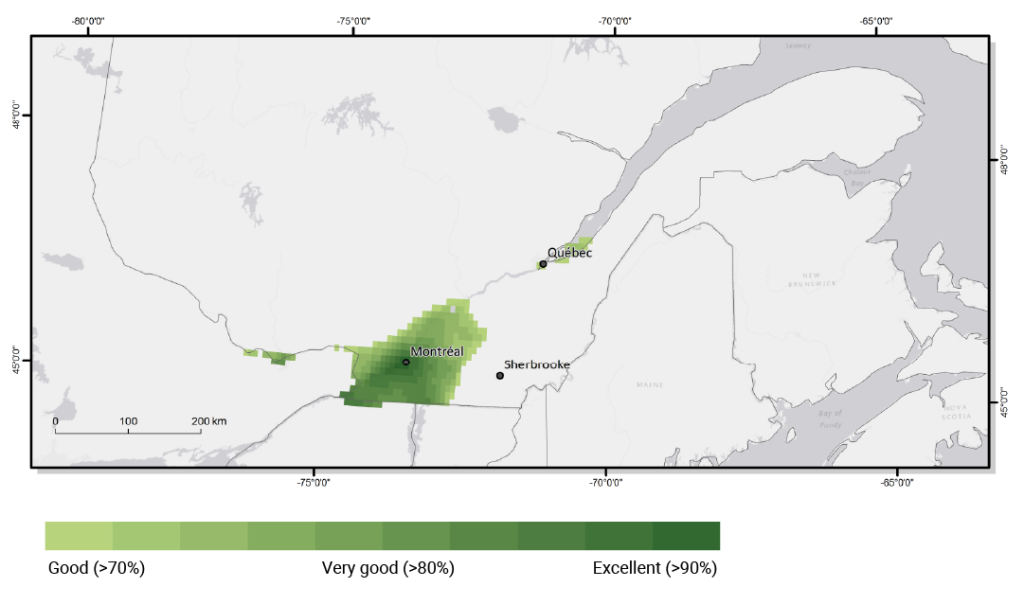

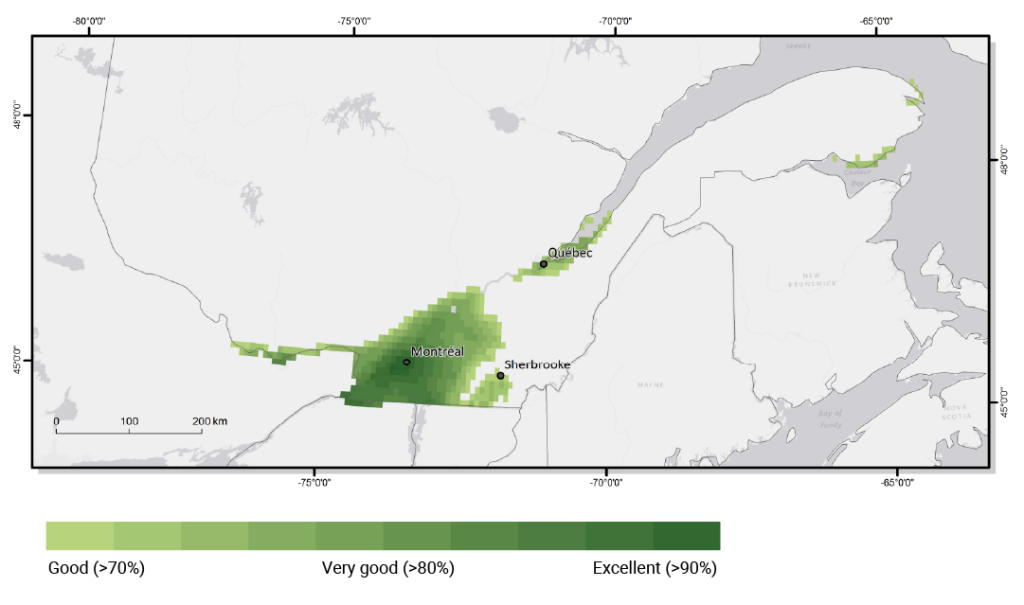

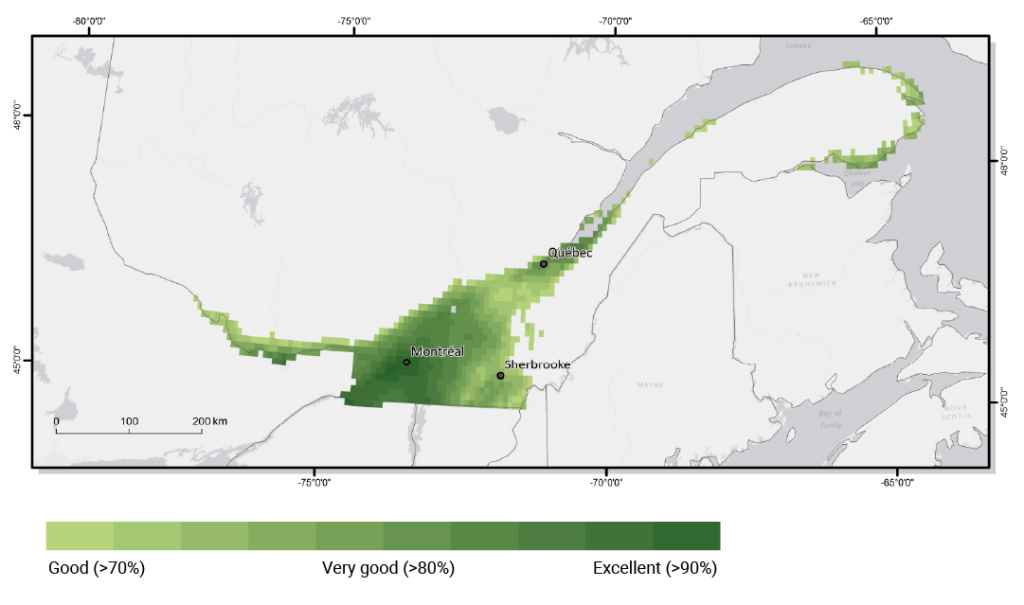

The agricultural and fisheries sectors will experience gains and losses

In Quebec, the agricultural, fisheries and aquaculture sectors could experience gains and losses in productivity, the emergence of new crop pests, and the northward migration of fish stocks due to climate change. Stakeholders in these sectors have initiated adaptation efforts by developing and using decision support tools that consider climate change in their practices.

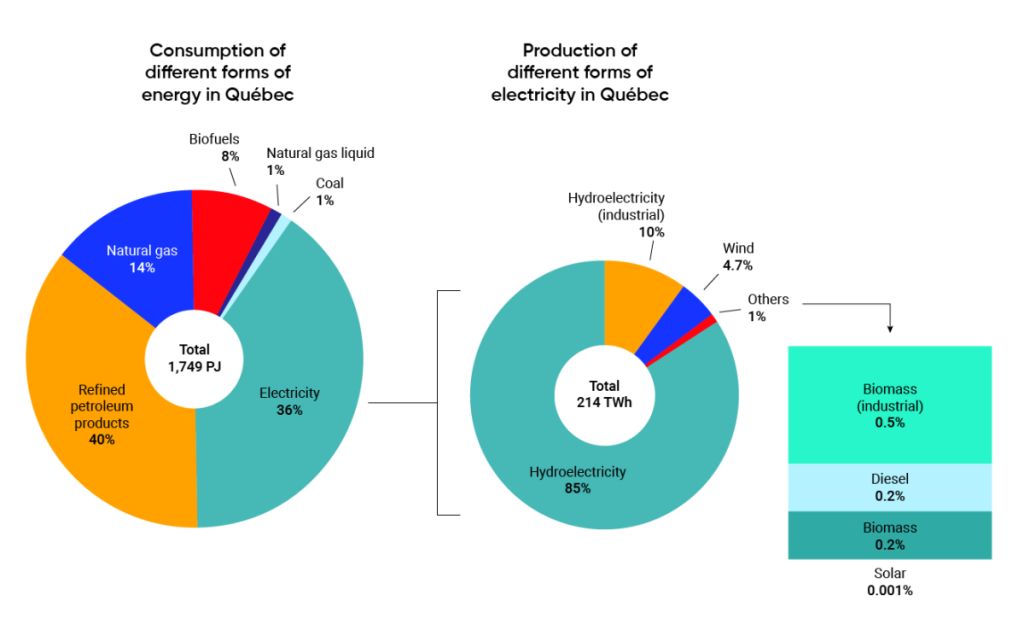

The energy, forestry and mining sectors will be particularly impacted by climate change

Quebec’s main natural resource sectors, namely energy, forestry and mining, will be particularly impacted by climate hazards. These hazards may impact operations, production, facilities and maintenance activities in these sectors. Producers are gradually adapting their decision-making processes and management methods to deal with climate change.

Tourism and financial sectors are feeling the impacts of climate change

Some industries, such as tourism and the insurance and financial service sectors are particularly sensitive to climate variations. In the last five years, a few companies, including some in the ski industry, have shown a proactive approach by implementing measures from a long-term planning perspective.