Natural Hazards

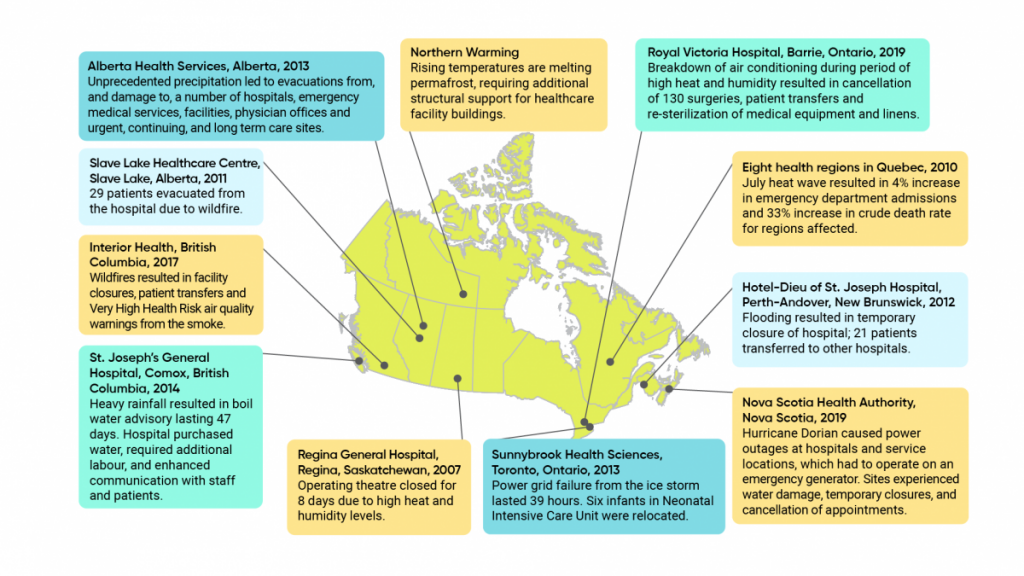

A range of natural hazards, including extreme weather events, routinely affect the health of Canadians, but sometimes effects on communities can be catastrophic. The number of days when the maximum temperature climbs over 30°C has increased in Canada, by about one to three days annually from 1948 to 2016 {3.4.1.2}. Such extreme heat increases deaths in Canadian cities by 2% to 13%, according to one study {3.4.2.1}. It is estimated that recent extreme heat events (“heat waves”) in Quebec have led to a significant number of deaths: 291 in a 2010 extreme heat event and 86 in a 2018 extreme heat event {3.4.2.2}. A severe extreme heat event in British Columbia in 2021 resulted in the death of 740 people. Extreme heat can also increase hospitalization for cardiovascular problems {3.4.2.4} and pregnancy complications, including premature birth, early delivery, miscarriage, and congenital abnormalities such as neural tube defects {3.4.2.6}. While some risks, such as injury and death from cold, may decrease, the increase in death due to heat is expected to outpace the reduced rates of death due to cold {3.6.3.2}.

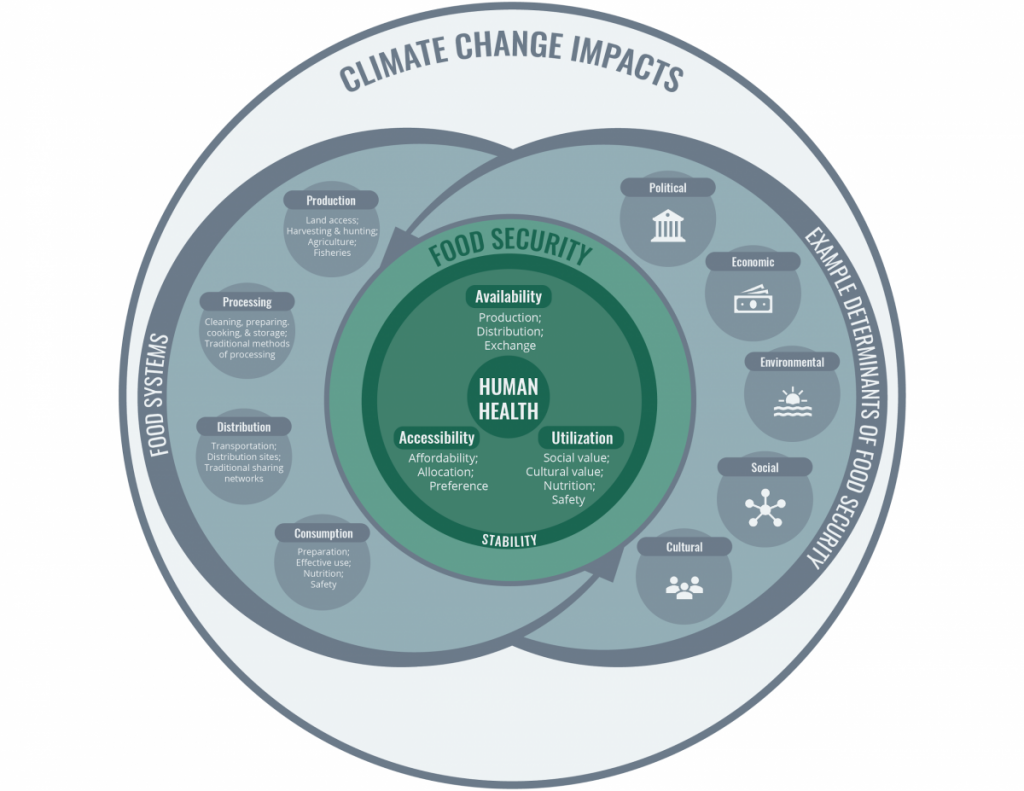

Drought increases fine dust in the air, which affects cardiovascular and respiratory health function. During droughts, winds spread pollen, fungi, mould, and bacteria, causing allergies and diseases. When rain falls after drought, pathogens can be carried into water bodies and drinking water systems, causing water-borne disease. Crop failures due to drought have many ripple effects on food security and food prices, as well as on the mental health of farmers and others in agricultural communities {3.7.2.4}.

Rainstorms and freezing rain result in pedestrian and motor vehicle-related injuries and other health risks due to infrastructure failure (such as power outages). Wind can also lead to accidents, especially if it reaches speeds of more than 70 km/h. Storms can lift massive amounts of pollen into the air, causing asthma outbreaks. In addition to washing viruses, bacteria, and parasites into surface and groundwater, leading to acute gastrointestinal illness, storms can spread the bacteria in airborne particles that cause legionellosis {3.9.2.5}.

Flooding can result in injuries, drowning, hypothermia, and electrocution. Because floodwaters can become contaminated from various sources, including sewage overflow, they can cause gastrointestinal and skin disease as well as infect wounds. Flooded homes can become unsafe because of mould, fungi, and bacteria. If power outages result from storms or floods, these can lead to accidents due to darkness, hypothermia from lack of heat, and carbon monoxide poisoning from using barbecues, camp stoves, and outdoor heaters indoors {3.9.2.6; 3.10.2.5}. Flooding can result in the evacuation of communities and cause long-term displacement, including from traditional territories, which can cause significant impacts on the health and well-being of affected Indigenous Peoples {2.4.1}. Studies show that flood victims can suffer mental health problems and cardiac events after a flood {3.10.2}.

Climate projections show increased extreme heat events in communities across Canada, and less precipitation in the summer throughout Southern Canada, with more droughts and water shortages in the summer in the Southern Prairies and the British Columbia Interior throughout the rest of this century {3.7.1}. While summer rain will decrease in Southern Canada, paradoxically, overall annual precipitation is increasing, especially in Northern Canada. More extreme precipitation events (unusually heavy rainfalls) are expected in the future {3.9.1}, leading to increased urban flood risk. Rising sea levels on the east coast of Canada are expected to submerge and erode coastlines.

With changing rainfall, snowfall, and temperatures, landslides are expected to become more common; the effect on avalanches has not yet been determined {3.11.1}. These hazards are rare in Canada but pose a risk of injury and death when they do happen. Avalanches are a risk for back-country skiers and snowmobilers, and landslides threaten homes and other infrastructure on hillsides {3.11.3}.

A growing threat to health in Northern communities is permafrost melting. Permafrost currently covers 40% of Canada’s landmass, but this area is expected to decrease by between 16% to 20% by 2090, compared with 1990 {3.11.1}. Thawing threatens the stability of buildings, roads, and communities in Northern Canada, with concomitant effects on transportation and access {2.4.1}. As it melts, permafrost may release infectious diseases from frozen wildlife carcasses and heavy metals such as mercury that can threaten health {3.11.2.3}.