This report provides an assessment of the risks of climate change to the health of Canadians and to the health care system, and of adaptation options. Led by Health Canada, it was released 2022.

Chapter 2

Key Messages and Summary

Summary

First Nations, Inuit, and Métis peoples in Canada are uniquely sensitive to the impacts of climate change because they tend to live in geographic regions experiencing rapid climate change and because they have a close relationship to and depend on the environment and its natural resources. The direct and indirect impacts of climate change on the health and well-being of First Nations, Inuit, and Métis are interconnected and far-reaching.

The changing climate will exacerbate the health and socio-economic inequities already experienced by First Nations, Inuit, and Métis peoples, including respiratory, cardiovascular, water- and foodborne, chronic and infectious diseases, as well as financial hardship and food insecurity. Natural hazards, coupled with unpredictable and extreme weather events, can result in temporary or long-term evacuations from traditional territories, in addition to greater risk of injury and death from accidents while out on the land. Infrastructure damage or instability due to climate change, particularly in Northern and remote locations, may restrict access to health systems and supplies. Climate change threatens First Nations, Inuit, and Métis peoples’ ways of life, resilience, cultural cohesion, and opportunities for the transmission of Indigenous knowledges and land skills, particularly among youth. Cross-cutting climate impacts will disrupt the livelihoods of First Nations, Inuit, and Métis peoples, families and communities, affecting their sense of identity and cultural continuity and compounding existing mental health issues. Indigenous knowledge systems and practices are key to First Nations, Inuit, and Métis peoples’ ability to observe, respond, and adapt to climate and environmental changes.

Key Messages

- First Nations, Inuit, and Métis peoples in Canada are uniquely sensitive to the impacts of climate change, given their close relationships to land, waters, animals, plants, and natural resources; tendency to live in geographic areas undergoing rapid climate change, especially Northern Canada; and greater existing burden of health inequalities and related determinants of health.

- The health impacts of climate change on First Nations, Inuit, and Métis peoples are interconnected and far-reaching. They result from direct and indirect impacts of climate change that exacerbate existing inequities, and affect food and water security, air quality, infrastructure, personal safety, mental well-being, livelihoods, and identity, as well as increase exposure to organisms causing disease.

- Health impacts are experienced differently within and between First Nations, Inuit, and Métis men, women, boys, girls, and gender-diverse people. Thus, research and adaptations must respect cultures, geography, local contexts, and the unique needs of these communities.

- First Nations, Inuit, and Métis peoples have been actively observing and adapting to changing environments in a diversity of ways since time immemorial. Indigenous knowledge systems and practices are equal to scientific knowledge and have been, and continue to be, critical to Indigenous Peoples’ survival and resilience.

- Indigenous knowledge systems are increasingly recognized, both nationally and internationally, as important in adapting to climate change, monitoring impacts at the local and regional level, and informing climate change policy and research.

- First Nations, Inuit, and Métis peoples are rights holders. Preparing for the health impacts of climate change requires that Indigenous Peoples’ rights and responsibilities over their lands, natural resources, and ways of life are respected, protected, and advanced through distinctions-based, Indigenous-led, climate change adaptation, policy, and research.

Overview of Climate Change Impacts on the Health and Well-Being of First Nations, Inuit, and Métis Peoples in Canada

| Health Impact or Hazard Category | Climate-related Causes | Possible Health Effects |

| Impacts on First Nations, Inuit, and Métis peoples and communities |

|

|

Chapter 3

Key Messages and Summary

Summary

Heatwaves, major floods, wildfires, coastal erosion, and droughts are examples of natural hazards whose frequency and intensity are influenced by climate change. These hazards can cause loss of life, injury and various health problems, damage to property, social and economic disruption, or environmental degradation. The impacts of natural hazards on human health are of particular concern. From heat stroke to cardiovascular and respiratory diseases, including psychological and social impacts, the health impacts of natural hazards can be serious and depend on complex processes involving individual, social, economic, and environmental factors. Canada has seen many examples of severe impacts from these hazards on the health and safety of the population in the last few years (e.g., heatwave and drought in British Columbia, Fort McMurray fires in Alberta, heatwaves and floods of 2018 in Ontario and Quebec, storms in the Maritime provinces). As climate change accelerates, these impacts on populations will increase unless effective adaptation measures are implemented to reduce them and to protect populations most at risk of being affected. Examples of these adaptation measures specific to each hazard already exist, and should be vigorously implemented by civil society, municipalities, health authorities, provinces, and the federal government.

Key Messages

- Many extreme weather events, and their health impacts on Canadians, are expected to increase in the coming decades, driven by the widespread warming. For example, extreme heat will become more frequent and more intense. This will increase the severity of heatwaves, and contribute to increased drought and wildfire risks. For most of Canada, precipitation is projected to increase, on average, although summer rainfall may decrease in some areas. Urban flood risks will increase due to more intense rainfalls (Canada’s Changing Climate Report, 2019).

- Deaths in Canada are projected to increase significantly by the end of the century due to the effects of rising temperatures (and extreme heat) if greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions continue to rise at the same rate seen over the past 30 years. Added to this are potential health effects of the changing pattern of some extreme weather events (e. g., wildfires, droughts, heatwaves, extreme precipitation) such as an increase in accidental injuries, anxiety and depression, water-borne diseases, cardiovascular problems, and respiratory illnesses. Workers directly exposed to those extreme events are already experiencing an increased burden of illness and injuries.

- Coastal regions face a multitude of increased risks to communities. Coastal flooding is expected to increase in many areas of Canada due to local sea level rise. The loss of sea ice in the Arctic, Eastern Quebec, and Atlantic Canada further increases the risk of damage to coastal infrastructure and ecosystems as a result of larger storm surges and waves (Canada’s Changing Climate Report, 2019).

- Some populations in urban and rural areas have limited access to the financial, social, health, and human resources needed to adapt to natural hazards influenced by climate change. Many First Nations, Inuit, and Métis communities experience a greater existing burden of health inequities and related determinants of poor health. This, combined with their close reliance on the environment for their sustenance, livelihoods, and cultural practices means they are uniquely sensitive to the impacts of climate change, including from natural hazards.

- Seniors are particularly at risk of suffering from the health impacts of climate change related events, such as heatwaves, cold snaps, drought, wildfire smoke, and floods. Age and chronic diseases are the main factors of vulnerability, and the fact that our society is aging rapidly will increase this risk in the next few decades. Seniors’ vulnerability can be compounded by loss of community cohesion, socio-economic inequality, and unhealthy behaviours.

- Provinces, municipalities, civil society, health authorities, and the federal government all have a key role to play in adapting to climate change. Despite progress on many efforts, adaptation measures are still lacking, especially for droughts, storms, and heavy precipitation. Moreover, populations at increased risk, and the preventable conditions that increase those risks, are often neglected by stakeholders when implementing adaptation measures.

- Many solutions that can reduce human exposure and vulnerability to natural hazards influenced by climate change are already known and should be better promoted. Those solutions include greening living environments, identifying at-risk areas, using early warning systems, improving access to resources, practicing integrated land-use planning, updating infrastructure, and raising public awareness.

- The pace, nature, and extent of adaptation measures must increase rapidly and substantially to reduce the current and future health impacts in Canada, including climate-related evacuations and forced displacement.

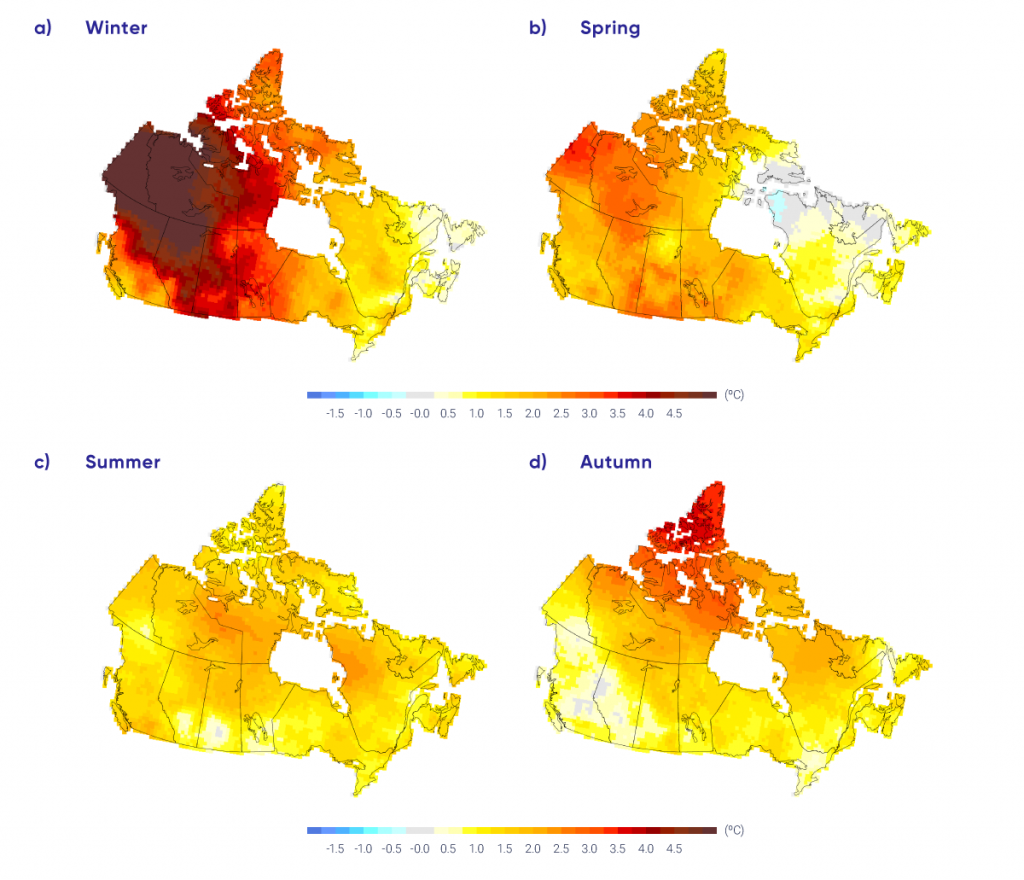

Figure 3.2

Observed changes (°C) in seasonal mean temperatures from 1948 to 2016 for four seasons.

Source

Zhang et al., 2019.

Overview of Climate Change Impacts of Natural Hazards on Health

| Health Hazard or Impact Category | Climate-Related Causes | Possible Health Effects |

| Temperature extremes and gradual warming |

|

|

| Extreme weather events and natural hazards |

|

|

Chapter 4

Key Messages and Summary

Summary

Climate change increases risks to the mental health and well-being of many people in Canada. Specific populations that can be disproportionally and inequitably affected include those experiencing health inequities based on race, culture, gender, age, socio-economic status, ability, and geographic location. These factors are encompassed within the social, biological, environmental, and cultural determinants of health that are amplified by climate change. Mental health can be impacted by hazards that occur over the shorter and longer term, such as floods, extreme heat events, wildfires, and hurricanes as well as drought, sea-level rise, and melting permafrost. Knowledge and awareness of climate change threats can also affect mental health and well-being, resulting in emotional and behavioural responses, such as worry, grief, anxiety, anger, hopelessness, and fear.

Mental health impacts of climate change may include exacerbation of existing mental illness such as psychosis; new-onset mental illness such as post-traumatic stress disorder; mental health stressors such as grief, worry, anxiety, and vicarious trauma; and a lost sense of place, which refers to the perceived or actual detachment from community, environment, or homeland. Impacts can also include disruptions to psychosocial well-being and resilience, disruptions to a sense of meaning in a person’s life, and lack of community cohesion, all of which can result in distress, higher rates of hospital admissions, increased suicide ideation or suicide, and increased negative behaviours such as substance misuse, violence, and aggression. Adaptation efforts that can reduce the mental health impacts of climate change include expanded communication and outreach activities and community preparedness, greater access to health care for those requiring assistance, and improved mental health literacy and training.

Key Messages

- The current burden of mental ill health in Canada is likely to rise as a result of climate change. Given the very large number of Canadians who experience mental health problems, the potential increase of mental ill health outcomes from future climate change is large.

- Climate change hazards that can affect the mental health of people in Canada include acute hazards such as floods, extreme heat events, wildfires, and hurricanes, as well as slow-onset hazards such as drought, sea-level rise, and melting permafrost. Secondary impacts of climate hazards (such as economic insecurity, displacement, food and water insecurity) can lead to ongoing stress, anxiety, and depression.

- Mental health impacts of climate change may include exacerbation of existing mental illness such as psychosis; new-onset mental illness such as post-traumatic stress disorder; mental health stressors such as grief, worry, anxiety, and vicarious trauma; and a lost sense of place, which refers to the perceived or actual detachment from community, environment, or homeland. Impacts can also include disruptions to psychosocial well-being and resilience, disruptions to a sense of meaning in a person’s life, and lack of community cohesion, all of which can result in distress, higher rates of hospital admissions, increased suicide ideation or suicide, and increased negative behaviours such as substance misuse, violence, and aggression.

- Climate change and related environmental change can cause complex emotional and behavioural reactions in individuals, that are not necessarily pathological. These environmental distress reactions, called psychoterratic syndromes, include ecoanxiety, solastalgia, and ecoparalysis.

- Climate change disproportionately affects the mental health of specific populations, including Indigenous Peoples; women; children; youth; older adults; people living in low socio-economic conditions (including the homeless); people living with pre-existing physical and mental health conditions; and certain occupational groups, such as land-based workers and first responders. For example, Indigenous Peoples are at greater risk of being displaced by climate-related hazards and this can result in a loss of community connections and loss of livelihoods that affect individual and collective well-being.

- Given the current high costs of mental illness to society, and the breadth of mental health impacts that are related to climate change, future costs borne by Canadians and health systems are expected to be large as the climate continues to warm.

- Access to mental health practitioners, mental health and health care facilities, social services, and culturally relevant mental health care information can prevent adverse mental health outcomes, improve outcomes, and enhance well-being in a changing climate. Rural, remote, and urban settings that currently face challenges providing mental health care will face increased demands for services from climate change impacts.

- Greater communication and outreach about the mental health impacts of climate change, enhanced community preparedness for possible impacts, broad access to culturally relevant health care to assist people in need, intersectoral and transdisciplinary collaboration on adaptation initiatives, and improved mental health literacy and training support efforts to prepare for climate change impacts on Canadians.

- Well-designed actions to mitigate greenhouse gas emissions and adapt to climate change — for example, active transportation, environmental stewardship, green infrastructure, and enhanced social networks and community supports — can also benefit mental health.

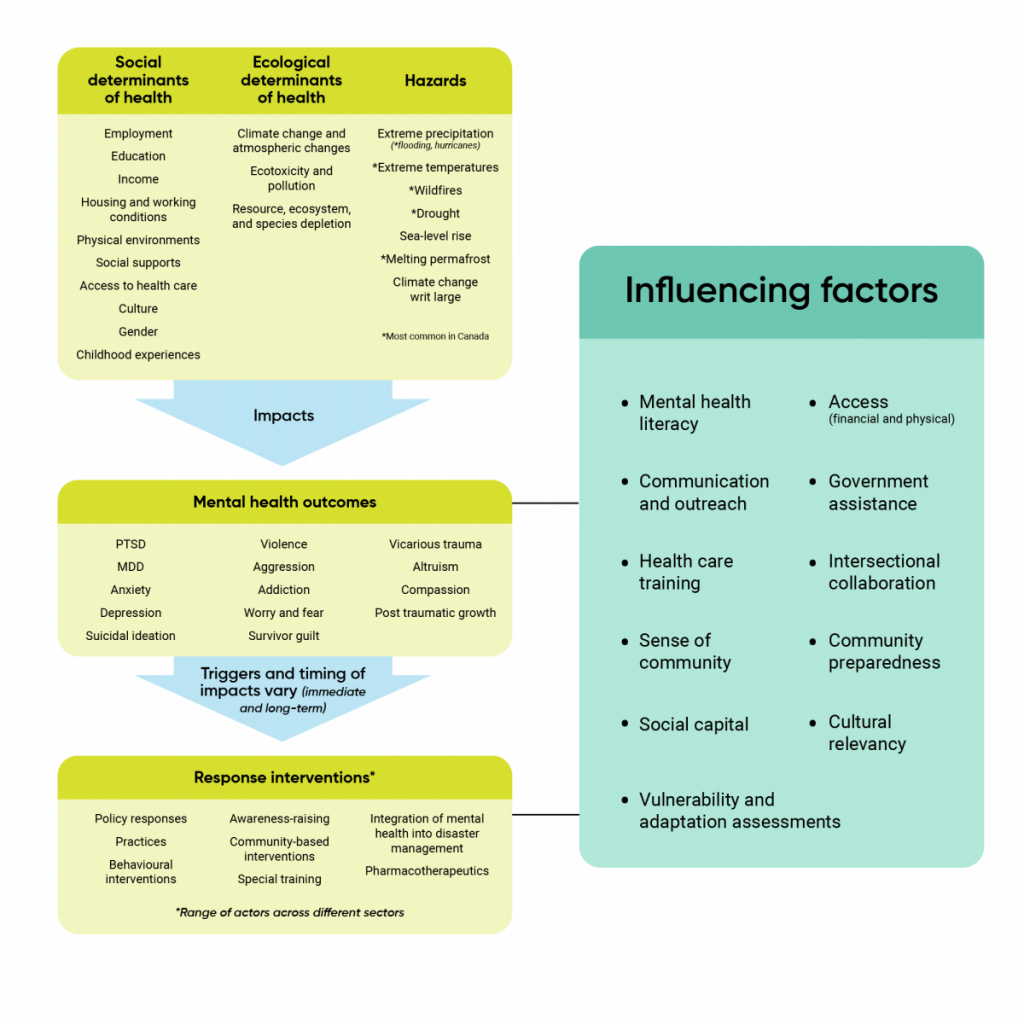

Figure 4.2

Factors that influence the psychosocial health impacts of climate change.

Source

Hayes et al., 2019.

Overview of Climate Change Impacts on Mental Health

| Health Impact or Hazard Category | Climate-Related Causes | Possible Health Effects |

| Mental health |

|

|

Chapter 5

Key Messages and Summary

Summary

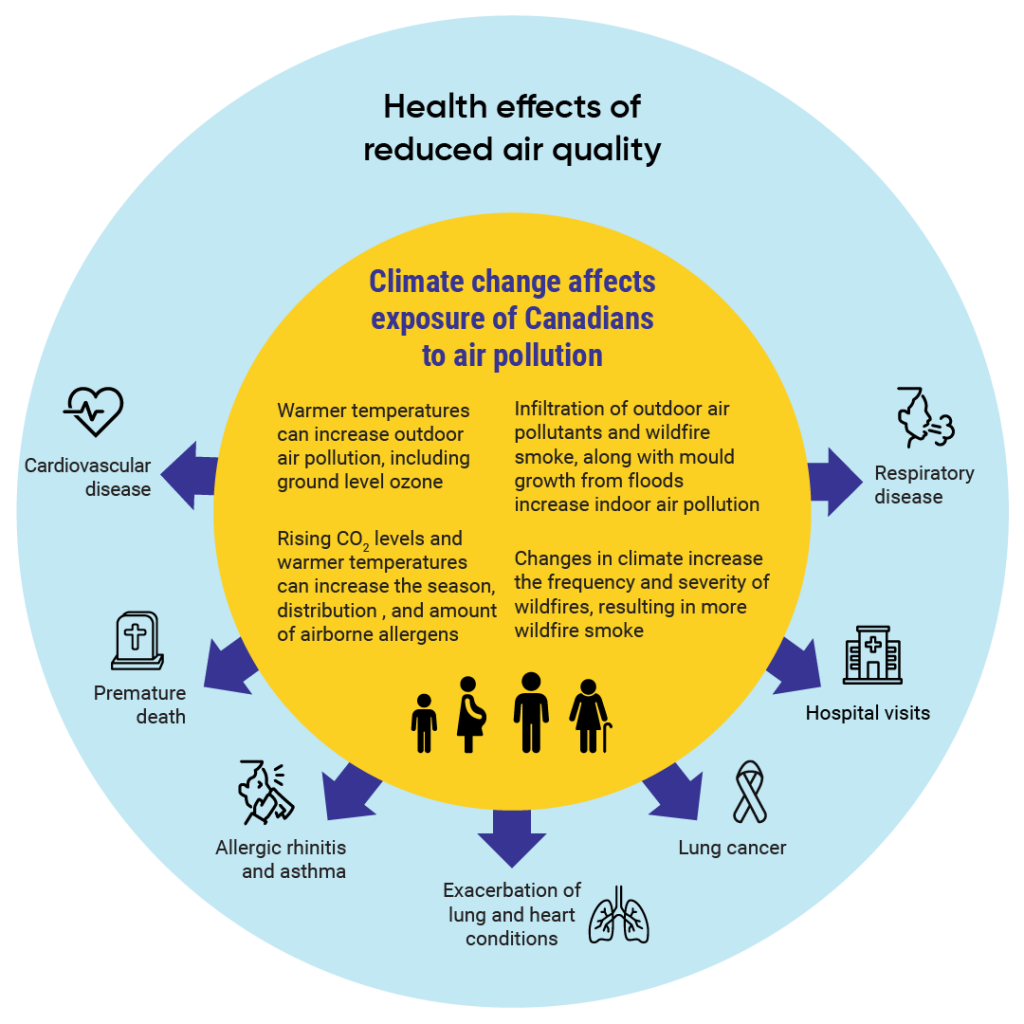

Climate change and air quality are intimately linked: changes in climate are affecting air quality in Canada, and several air pollutants contribute to climate change. Exposure to key air pollutants, including fine particulate matter and ozone, increases the risk of adverse health outcomes, ranging from respiratory symptoms to development of disease and premature death. A warming climate is expected to worsen air pollution levels in Canada. As the frequency and severity of wildfires are expected to increase due to climate change, emissions from wildfires represent one of the most significant climate-related risks to air quality in Canada. Climate change can also affect indoor air quality when elevated levels of outdoor air pollutants infiltrate buildings or when mould accumulates following extreme weather events, such as floods. Changes in the climate are affecting airborne allergens such as pollen by expanding the geographic distribution of plant species, extending pollen seasons, and increasing pollen counts.

Some groups are at increased risk of health impacts related to air pollution, including children, seniors, Indigenous Peoples, those with pre-existing conditions such as asthma or cardiac disease, and populations living in high air pollution areas. Mitigation efforts to reduce emissions of greenhouse gases can have substantial population health co-benefits related to improved air quality. These co-benefits can help offset the costs of climate mitigation, providing support for accelerated implementation of mitigation policies. Adaptation efforts that would prevent or alleviate the climate-related health impacts of air pollution include limiting exposure to air pollutants, including through the use of emergency shelters during wildfires; providing daily forecasts of air quality, wildfire smoke, and aeroallergens, such as the Air Quality Health Index; and preventing floods and ensuring that buildings have adequate ventilation and air filtration.

Key Messages

- Climate change and air quality are linked: overall, a warmer climate is expected to worsen air pollution in Canada, and some air pollutants contribute to climate change. If air pollution emissions remain unchanged, a warming climate will likely increase ozone levels in heavily populated and industrialized areas, including Southern Ontario and Southwestern Quebec. Projected effects on fine particulate matter are more modest and uncertain.

- The health impacts of air pollution in Canada, including premature death and disease, are expected to worsen in the future due to the influence of climate change. Unless these impacts are offset by reducing air pollution, hundreds of deaths annually are expected to result by mid-century. Today, air pollution is a leading environmental cause of death and illness in Canada, resulting in an estimated 15,300 deaths a year, with an economic value of $114 billion annually.

- Canada needs to prepare for a future with more wildfires. Increasing wildfire emissions are one of the most significant climate-related risks to air quality in Canada. Wildfire smoke, which can spread over vast areas of the country, contributed to an estimated 620 to 2700 deaths annually in Canada from 2013 to 2018. The public health burden of wildfire smoke is expected to increase in the future due to climate change.

- Climate change will increase the length of airborne allergen seasons, pollen counts, and the geographical distribution of allergens. Respiratory allergies and asthma are expected to affect more people more often in the future, increasing costs to the health system.

- Climate change can affect indoor air quality through increased infiltration of outdoor pollutants and allergens, and as a result of weather events such as floods that cause mould growth in buildings. At the same time, energy retrofits of buildings without adequate ventilation can reduce indoor air quality. Key adaptation strategies for indoor air include ventilation, filtration, and controlling pollutant sources.

- Daily forecasts of air quality, wildfire smoke, and airborne allergens presented in accessible formats, such as the Air Quality Health Index, are important tools to protect community health and a key adaptation strategy to inform populations at higher risk of health impacts resulting from a changing climate.

- Mitigation measures targeting climate pollutants, including methane and black carbon (soot), can have important immediate and long-term co-benefits for the health of local populations by reducing air pollution. The air quality benefits of these mitigation measures can help to offset the costs of climate action. Climate mitigation measures that improve air quality will also help avoid thousands of deaths annually in Canada by the middle of the century.

Health risks of climate change impacts on air pollution.

Chapter 5

Overview of Climate-Related Health Impacts Associated with Air Quality

| Health Impact or Hazard Category | Climate-Related Causes | Possible Health Effects |

| Air quality |

|

|

Chapter 6

Key Messages and Summary

Summary

Climate change is affecting the risk from infectious diseases. There is evidence that the recent emergence of Lyme disease in Canada has been driven by climate warming, making more of Canada suitable for the ticks that carry the disease. Emergence of other insect-borne diseases, such as eastern equine encephalitis, could have been facilitated by a warming climate, and epidemics of West Nile virus infection have likely been driven by variability in weather and climate, which will increase with climate change. The risk from a very wide range of other infectious diseases is also known to be sensitive to weather and climate. Changes to geographic and seasonal patterns of these diseases in North America, and increased risk of importation of climate-sensitive diseases from further afield, are likely to pose increased risks to Canadians in coming decades. Adaptation measures include assessments of risk and vulnerability, integrated surveillance and early warning systems using emerging technologies, and a “One Health” approach that integrates human, animal, and environmental health.

Key Messages

- Under climate change, many diseases considered “climate-sensitive” are more likely to emerge or re-emerge globally and in Canada. These diseases include those transmitted by arthropod vectors (such as West Nile virus, Lyme disease), those directly transmitted from animals (zoonoses such as rabies, hantavirus pulmonary syndrome), those directly transmitted human-to-human (such as seasonal influenza, enterovirus infections), and those that can be acquired by inhalation from environmental sources (such as Cryptococcus infection, Legionnaires’ disease).

- Infectious diseases new to Canada may spread northward from the United States, and from elsewhere in the world, carried by people and goods, or by wild animals. The indirect socio-economic effects of climate change may affect the capacity of nations to prevent and control infectious diseases globally, increasing the likelihood that new diseases will come into Canada through human travel and migration.

- Climate change is expected to make the Canadian environment more suitable for arthropod vectors (such as mosquitoes and ticks) and transmission of new infectious diseases. For example, mosquito-borne diseases already in Canada such as West Nile virus, which usually cause a limited number of infections each year, may produce epidemics under a more variable climate with more frequent extreme weather events.

- Potential effects of climate change on infectious diseases are identified by modelling studies, while disease surveillance has identified changes in occurrence of infectious diseases, and in some cases linked these changes to recent effects of climate change. These studies are largely restricted to diseases that humans acquire from arthropod vectors (insects and ticks) and directly from animals.

- Canada has high adaptive capacity to cope with infectious diseases given its robust national public health surveillance and response tied into national and international networks, a strong health system, and capacity for technological innovations. Canada is also a leader in “One Health” approaches that consider human, animal, and environmental factors together, using knowledge from many disciplines and sectors. Such approaches are essential to planning for emerging and re-emerging infectious diseases, including those related to climate change.

- Canada is also increasing its capacity to respond to effects of climate change on infectious diseases. This capacity will be enhanced by big data and modern genomic technologies, Earth observation from satellites, web crawling, and “citizen science” approaches to surveillance for climate change impacts on infectious diseases.

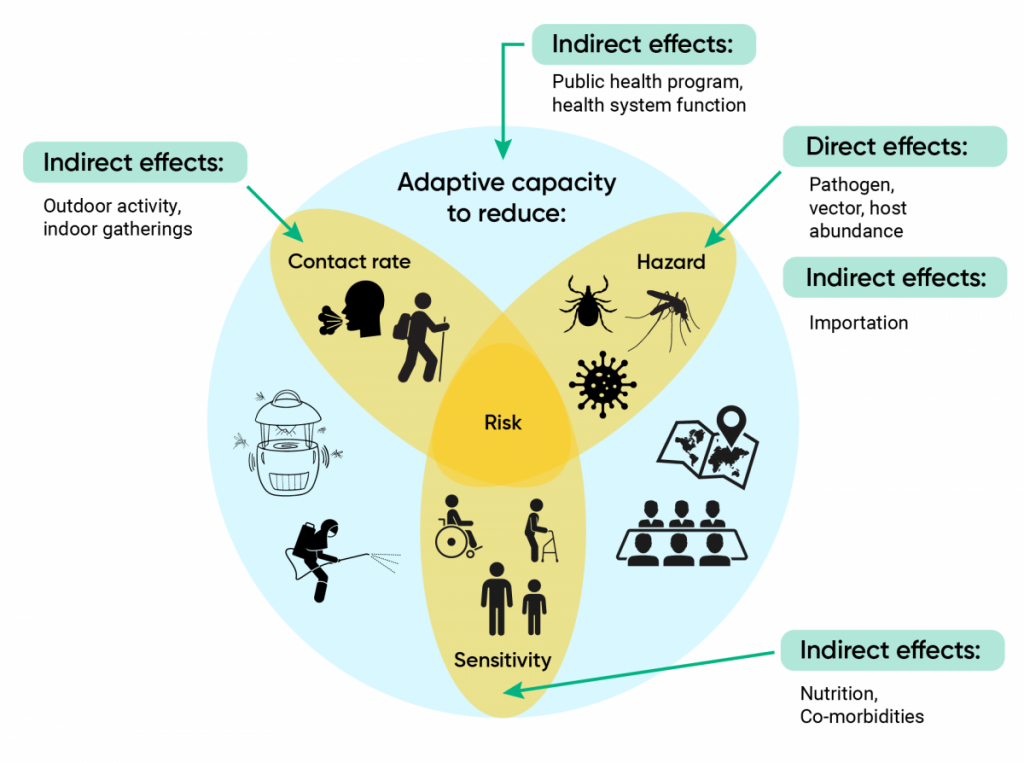

Figure 6.1

Components of vulnerability to infectious diseases in the context of climate change.

Figure 6.1

The three intersecting components of risk are hazard, contact rate (which, with hazard, determines exposure), and sensitivity. Adaptation (represented by the blue background disc) depends on the capacity to minimize, and respond to changes in each of these three components of risk. Green arrows show direct and indirect effects of climate change.

Overview of the Impacts of Climate Change on Infectious Diseases

| Health Impact or Hazard Category | Climate-Related Causes | Possible Health Effects |

| Infectious diseases transmitted by arthropod vectors |

|

|

| Infectious diseases directly transmitted by animals (zoonotic diseases) |

|

|

| Infectious diseases acquired by inhalation from environmental sources |

|

|

| Emerging infectious diseases |

|

|

List of Acronyms

CSGV California serogroup viruses

CVV Cache Valley virus

EEEV eastern equine encephalitis virus

EIP extrinsic incubation period

GCM global climate models

GHG greenhouse gas

GOARN Global Outbreak Alert and Response Network

GPHIN Global Public Health Intelligence Network

HFMD hand-foot-and-mouth disease

IHR International Health Regulations

JCV Jamestown Canyon virus

JE Japanese encephalitis

LACV La Crosse encephalitis virus

MCDA multi-criteria decision analysis

RCP representative concentration pathways

RMSF Rocky Mountain spotted fever

RRA rapid risk assessment

RVFV Rift Valley fever virus

SINV Sindbis virus

SLEV St. Louis encephalitis virus

SSHV Snowshoe Hare virus

USUV Usutu virus

VEE Venezuelan equine encephalitis

WGS whole genome sequencing

WHO World Health Organization

WNV West Nile virus

YF yellow fever

Chapter

Key Messages and Summary

Summary

Climate change is expected to result in fluctuations in water quantity, degraded water quality, increased flood and drought risks, as well as, a greater burden of climate-related waterborne disease. The impacts of sea-level rise and loss of ice in Canada are likely to be significant. Not all Canadians will experience these impacts equally. First Nations, Métis, and Inuit communities, many of which already face water insecurity, are expected to be disproportionately affected, as are rural and remote communities that have only basic water and sewage infrastructure.

The health impacts associated with climate change effects on water quality and quantity are not inevitable. Through effective mitigation and adaptation, they can be reduced. Canadians can better adapt to these anticipated impacts and protect health by assessing local climate risks and vulnerabilities, developing adaptation plans, improving surveillance systems, building climate-resilient water systems, and promoting intersectoral collaboration to protect water resources and address climate related risks.

Key Messages

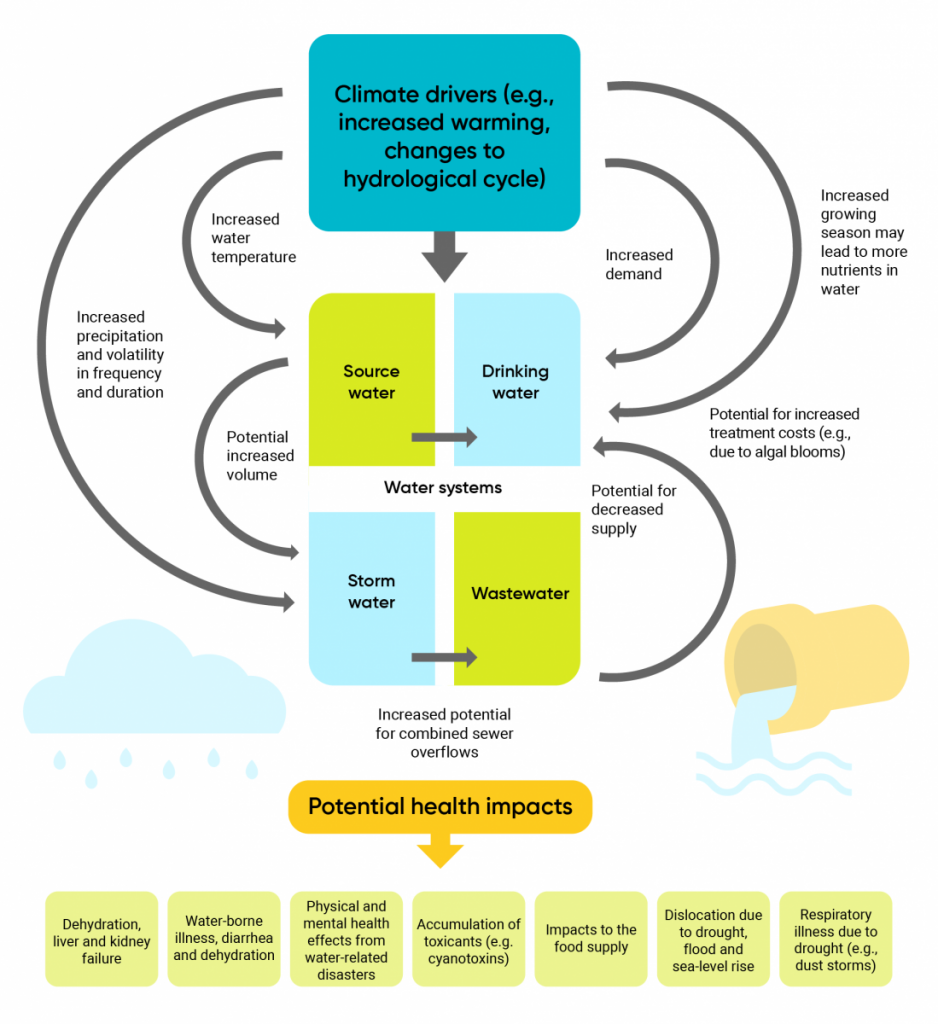

- Changes in precipitation and temperature due to climate change will result in impacts on water quality and quantity and disrupt both natural water systems (rivers, lakes, oceans) and human drinking water and wastewater systems, thereby increasing risks to the health of Canadians. The extent and intensity of these changes will vary by region and season.

- Water-related health risks associated with climate change include threats to drinking water and irrigation supplies; increases in water-borne diseases (e.g., cryptosporidiosis, giardiasis, campylobacteriosis); physical injuries and mental health impacts from extreme weather events such as floods and droughts; and threats to health and well-being due to the socio-economic and environmental consequences of water insecurity.

- Climate change–related water and food shortages, coupled with increasing population growth in climate vulnerable regions of the world with fewer resources, could affect Canada through regional and international migration.

- Adaptation to the anticipated impacts of climate change on water resources and human health can help protect Canadians from future risks. Adaptation will require broad multi-sectoral action and coordination among, for example, public health practitioners and service providers, and water and wastewater managers.

- Indigenous Peoples are among those most affected by the degradation of water resources, but they also possess countless generations of accumulated knowledge, which can be applied to protect health. Partnerships among Indigenous communities, health authorities, and water managers are needed to identify the population-specific health impacts of climate change impacts on water resources and to implement effective adaptation options informed by traditional knowledges and cultural needs.

- More information is required on the current burden of disease in Canada related to the climate change impacts on water resources and related hazards, and on the projected health risks from further warming. Research is also needed on the most effective ways to adapt to increasing stresses on drinking water systems and on needed public health interventions, including the communication of risks to the public. Better models for regional drought and flood prediction are needed.

- Health authorities can increase our understanding of climate change impacts on water resources and health, as well as potential adaptation options, by conducting local and regional vulnerability and adaptation assessments related to climate change and health. By doing so health authorities can improve their preparedness, maximize the health benefits of cross-sector collaboration, and build climate resilience within their communities.

Figure 7.1

Examples of the direct and indirect ways climate change can alter water quality and quantity and affect health.

Chapter 7

Overview of the Health Impacts of Water Quality, Quantity, and Security in the Context of Climate Change

| Health Impact or Hazard Category | Climate-Related Causes | Possible Health Effects |

| Water quality, quantity, and security |

|

|

Chapter

Key Messages and Summary

Summary

Changes in climate are affecting food security and food safety in Canada. Climate change is increasing risks of food insecurity through disruptions to food systems, rises in food prices, and negative nutritional effects. Precipitation, temperature, and extreme weather events are projected to increase the introduction of pathogens (viruses, bacteria, and parasites) to food, causing food-borne illness. Chemical contaminants that have harmful health effects may also be introduced into Canada’s food systems more frequently through various climate-sensitive environmental exposure pathways. The impacts of climate change on food security and food safety will not be equitably distributed, and Canada’s Northern region and Indigenous Peoples will likely experience the most severe effects. Adaptation measures include monitoring of health outcomes related to food safety; conducting vulnerability and adaptation assessments that address climate-related impacts to food security and food safety; utilizing both Western science and Indigenous knowledge; developing adaptation plans within all levels of government and in all regions, particularly in Northern Canada; conducting risk communication and education; and tackling root causes of vulnerability.

Key Messages

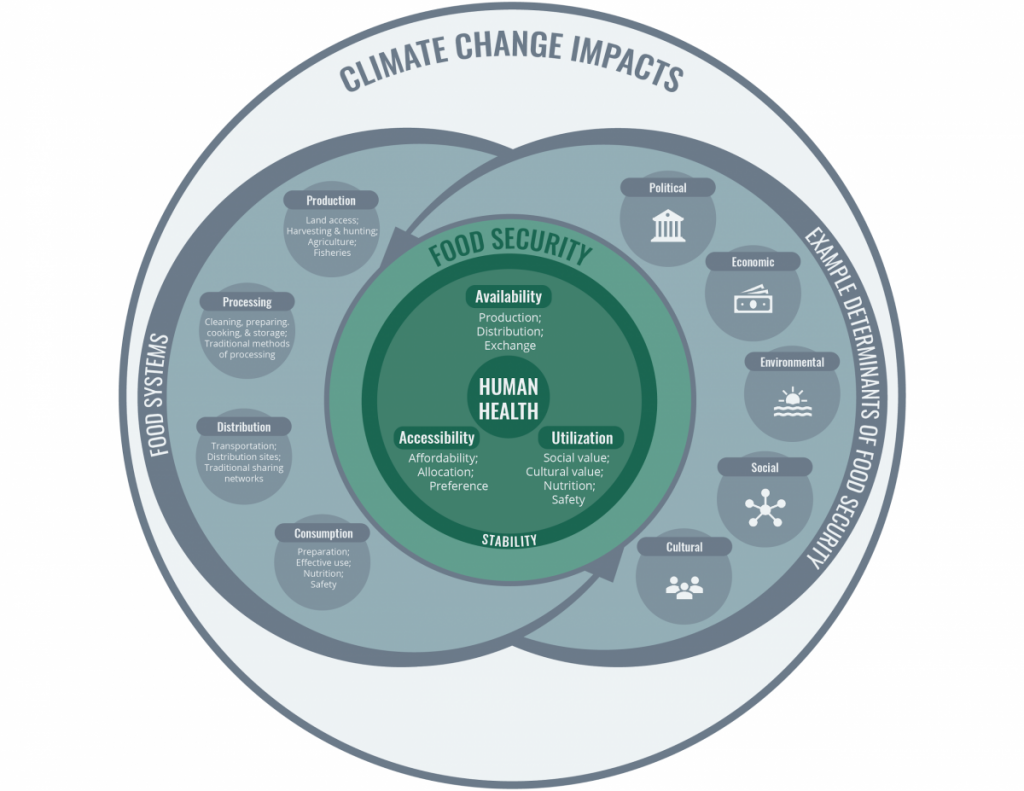

- Warming temperatures, changing precipitation patterns, and more frequent and severe extreme weather events will increase risks to key components of food systems in Canada, such as the production, processing, distribution, preparation, and consumption of food.

- Climate change impacts on food systems, rises in food prices, and negative nutritional effects have already negatively influenced food security and food safety, both of which have important implications for human health. Globally, climate change is projected to have negative effects on the nutritional content and overall yield of some agricultural commodities, particularly subsistence crops including grains and legumes. Changes in biodiversity from climate change may also result in nutritional challenges, for example, from declining availability of traditional food sources. As a result, climate change is projected to affect the health of Canadians by affecting the amount of nutrients they obtain from their food, as well as the stability of food availability, accessibility, and use.

- Climate change is projected to exacerbate existing food safety challenges in Canada and create new ones. Precipitation, temperature, and extreme weather events affect the introduction of pathogens to foods and their ability to grow to levels that cause food-borne illness. Climate change may also affect human behaviours, such as food handling and consumption practices (such as barbeques, picnics).

- Climate change impacts on food security and food safety vary greatly across Canada, reflecting underlying societal, cultural, environmental, and economic factors and inequities. While it is difficult to estimate the precise magnitude of current and future climate change impacts on food insecurity, these impacts are expected to exacerbate health-related risks for Canadians.

- Climate change may increase the exposure of Canadians to chemical contaminants, such as persistent organic pollutants and heavy metals that can have harmful health effects. These chemical contaminants can be introduced into Canada’s food systems through various environmental exposure pathways and then accumulate in plant and animal tissues that are consumed. Many of these chemicals can exacerbate existing health risks for Canadians and create new ones, which underlines the importance of Canada’s surveillance programs.

- Climate change is affecting Indigenous food systems and contributing to declining availability, accessibility, and quality of traditionally harvested foods, which play an important role in community and individual health and well-being. Climate change has already affected nutrition, mental health outcomes, and food sovereignty. Indigenous food security must be understood within the context of historical and ongoing colonialism. Indigenous self-determination and the gendered and intergenerational transmission of Indigenous knowledge are central to Indigenous food security and sovereignty and needed adaptation actions.

- Adaptation actions that increase food system resilience, including collaboration of health authorities among a broad range of food system actors and sectors, are necessary to minimize risks to human health from climate change. Efforts are underway across Canada to respond to and prepare for the impacts of climate change on food systems in order to protect and support health and well-being. Further adaptations will reduce future risks.

Figure 8.1

Conceptual framework outlining the relationships among food security, food safety, and health in a changing climate.

Chapter 8

Overview of Climate Change Impacts on Food Safety and Security

| Climate Health Risk or Hazard Category | Climate-Related Causes | Possible Health Effects |

| Food security |

|

|

| Food safety |

|

|

Chapter

Key Messages and Summary

Summary

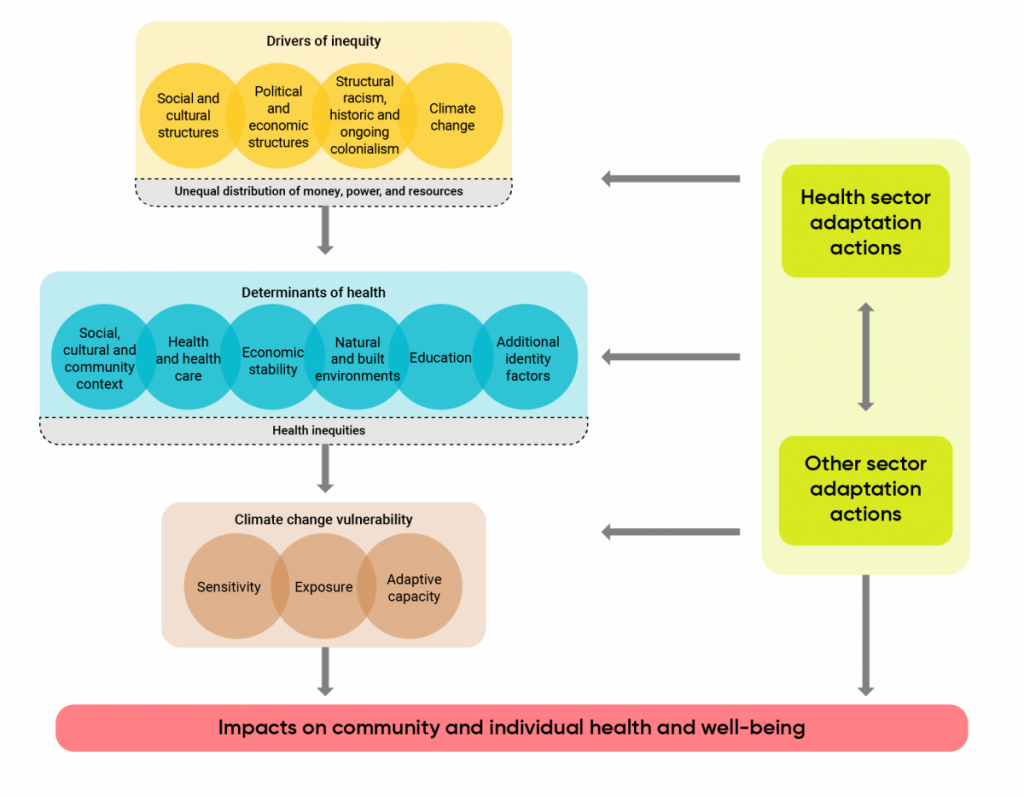

Changes in climate are exacerbating existing health inequities and creating conditions for new inequities to emerge. The health effects associated with climate change will not be experienced uniformly. Vulnerability to health impacts of climate change is determined by the exposure to climate change hazards, the sensitivity to possible impacts, and the capacity to respond to, or cope with them. At the individual level, these three factors are influenced by determinants of health, such as socio-economic status, housing quality, and education. Determinants of health interact and intersect with inequities in complex ways that render the experiences of diverse groups and individuals unique. Structural systems of oppression, such as racism and colonialism, also influence an individual’s vulnerability to climate-related health risks. Therefore, effective adaptation measures must be intersectional and equity-based. If adaptation efforts are not carefully planned, adaptation efforts may benefit only part of the population, and inadvertently worsen existing inequities. Resilience and asset mapping, vulnerability mapping, equity impact assessments, and meaningful and inclusive community engagement and communications can all contribute to equity-centred adaptation measures.

Key Messages

- Climate change can exacerbate existing health inequities, defined as avoidable and unjust differences in health. These inequities — for example, disproportionate impacts on health from extreme heat — can increase the health risks from climate change for some individuals and populations. Knowledge gaps and data limitations make it difficult to assess and measure how climate change has already affected, and will continue to affect, health equity in Canada.

- The pathways through which climate change affects health inequities are complex and dynamic. These pathways often involve the conditions and factors that affect a person’s health, known as determinants of health (such as, income, education, employment, and working and living conditions), which can increase or decrease an individual’s exposure or sensitivity to climate-related health hazards and can create barriers that limit their ability to take protective measures.

- Structural systems of oppression (such as, racism, heteronormativity, and ableism) that result in health inequities are underlying drivers of vulnerability to climate change.

- Health equity should be an important focus of climate change and health vulnerability and adaptation assessments and related knowledge development activities. Mapping tools (asset mapping, vulnerability mapping), enhanced data collection, and inclusive community engagement will help identify populations and regions at increased risk, and better inform adaptation measures.

- Climate change adaptation measures meant to protect human health are not experienced in the same way across populations and communities. In the absence of careful planning, adaptation efforts may benefit only part of the population and inadvertently worsen existing health inequities.

- Health equity can be increased and determinants of good health strengthened through adaptation. Public health authorities should ensure that adaptation measures are planned and implemented so that people who are disproportionately affected by a warming climate benefit from them.

- Ensuring inclusive, equitable, and community-based participation in the adaptation process is critical for designing and implementing effective adaptation actions that protect the health of all Canadians. Participation of racialized and marginalized individuals and communities that already experience a disproportionate burden of illness and health inequities is required.

- Climate change mitigation and adaptation measures implemented outside of the health sector may affect determinants of health and health outcomes, in either positive or negative ways. Public health authorities can ensure that climate action supports health equity and related positive health outcomes in Canada through collaboration across jurisdictions, sectors, and disciplines.

Figure 9.1

Climate change and health equity framework.

Chapter 10

Key Messages and Summary

Summary

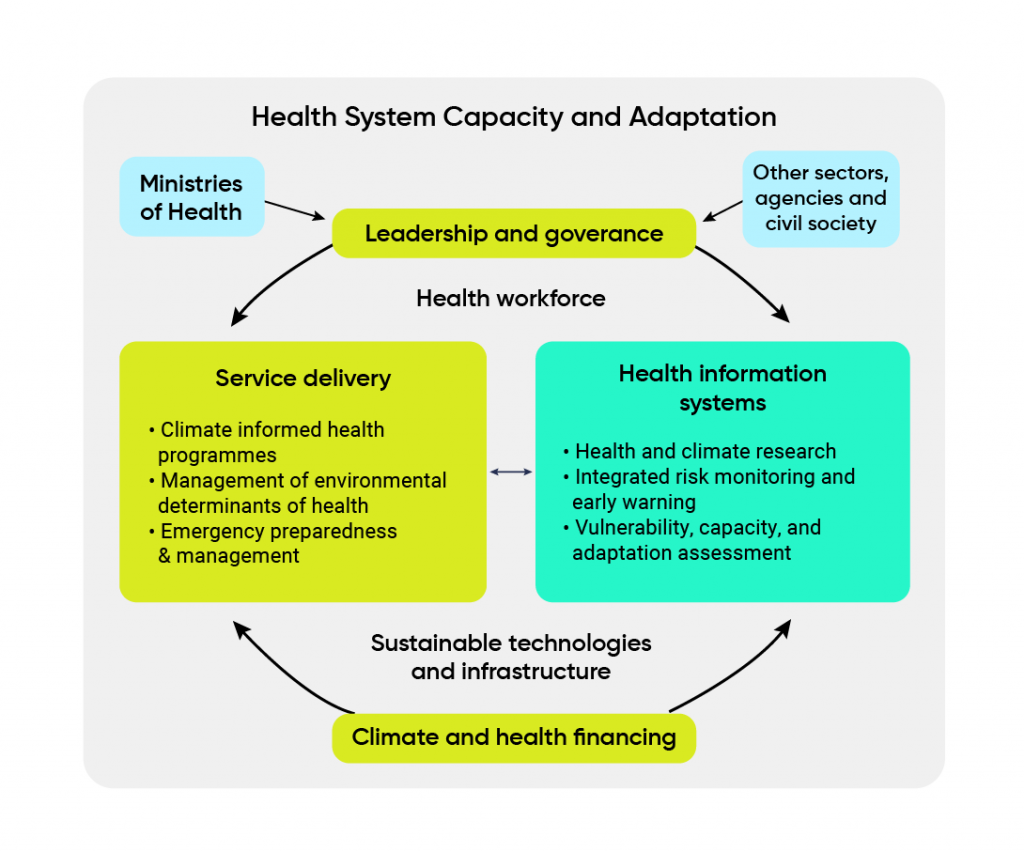

Changes in climate are affecting the health of Canadians and their health systems. Recent floods, wildfires, extreme heat events, and severe storms have had impacts on health facilities and disrupted care to those in need. Adaptation measures such as assessments of risks and vulnerabilities, integrated surveillance and warning systems, health professional training, and public education can help prepare Canadians and build the climate resilience of health systems. Well-designed efforts to adapt to climate change impacts and reduce greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions within and outside of the health sector can result in very large and near-term co-benefits to health. Many health authorities in Canada are increasing adaptation efforts. However, disparities in efforts exist across the country and adaptation needs to be rapidly scaled up to protect health as Canada continues to warm.

Key Messages

- The effects of climate change on health and on health systems in Canada are already evident and will worsen if existing vulnerabilities are not addressed and if gaps in health adaptation are not closed.

- Efforts to adapt to climate change — focusing on its health impacts — can significantly reduce current and future impacts on individual Canadians, communities, and health systems.

- Climate change impacts on health pose significant economic costs to Canadians, and these costs will increase in the future unless Canada adapts effectively.

- Canadian health authorities are undertaking a range of measures to adapt to climate change but are still lagging in many climate change and health actions to respond to the growing risks to Canadians.

- Many health authorities are not considering key drivers of vulnerability for specific population groups and therefore may not be addressing important aspects of adaptation for people disproportionately affected, such as First Nations, Inuit, and Métis peoples, racialized populations, seniors, women, and those of lower socio-economic status.

- Individual Canadians need to increase preparedness for climate change impacts. Many still need to take necessary measures to protect themselves and their loved ones from growing risks to health.

- Health authorities must take measures to increase the climate resilience of health systems. This means ensuring they remain operational when threatened by hazards and sustainable over the longer term, which is one of the most effective ways to protect human health and well-being from the impacts of climate change. Adaptation measures must be scaled up rapidly and substantially if current and future health impacts are to be reduced.

- Protecting Canadians from climate change requires a commitment to Indigenous leadership and partnership in research and adaptation efforts, including engaging with Indigenous Peoples in a meaningful way and recognizing and using Indigenous knowledge in a respectful way.

- Major co-benefits to human health can be achieved when decision makers in other sectors (such as water, transportation, energy, housing, urban design, agriculture, conservation) promote health and health equity through the design and implementation of actions to adapt to climate change and mitigate GHGs.

- Strong measures to reduce GHGs are needed to protect Canadians, their communities, and their health systems from climate change. The health sector can show leadership in reducing its carbon footprint and improving environmental sustainability, while building resilience to future climate change impacts.

Figure 1.3a

Climate resilience of health systems functions.

Source

WHO, 2022, Working paper on measuring climate resilience of health systems.