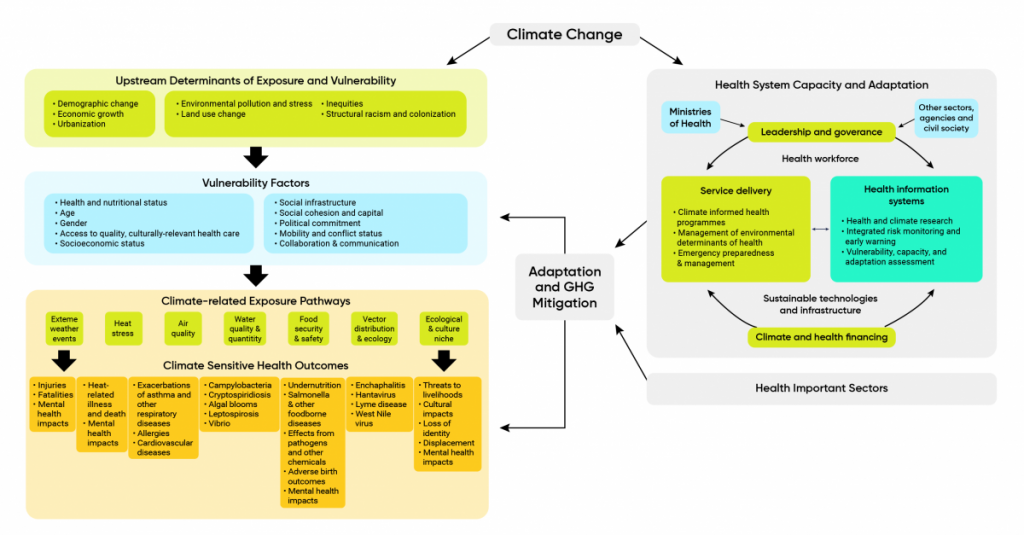

Evidence of the risks to health from climate change and the pathways through which people are affected has grown with publication of reports from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) (Confalonieri et al., 2007; Smith et al., 2014; WHO, 2014; WHO, 2018) and related studies (Watts et al., 2015; Crimmins et al., 2016; Watts et al., 2018). Climate drivers of poor health that need to be understood to adapt are complex and mediated by a range of determinants of health and other situational, behavioural, and organizational factors (Figure 1.3). This makes the management of current risks to health, and of projected impacts, by public health officials challenging and requires close partnerships with officials within and outside the health sector.

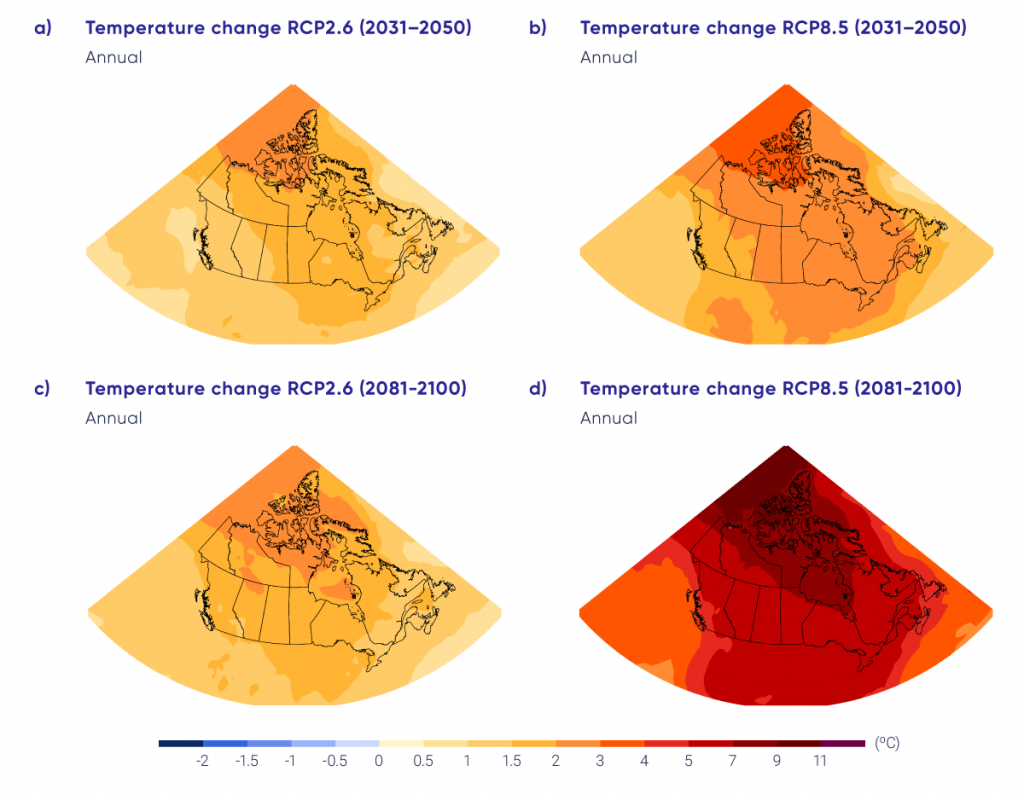

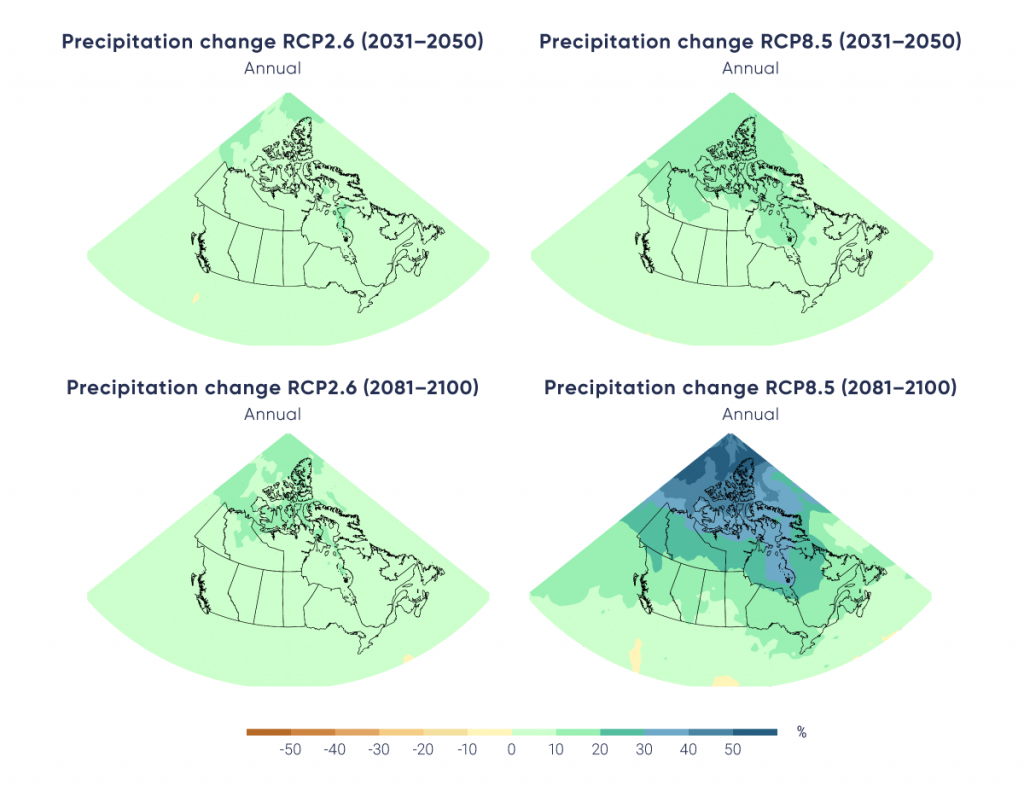

Upstream drivers related to trends such as population growth, economic growth, urbanization, colonialism, and racism can put pressures on a range of factors that can increase or decrease vulnerability to the health impacts of climate change. Health can be affected by climate change directly or indirectly, through a range of exposure pathways, as temperatures continue to rise, precipitation patterns change, and the frequency and severity of extreme weather events increase, resulting in more natural disasters (IPCC, 2012; Smith et al., 2014; Watts et al., 2015; Hoegh-Guldberg et al., 2018).

Direct impacts on health can include non-communicable diseases (e.g., respiratory and cardiovascular diseases, mental health impacts) and injuries and deaths associated with extreme weather events such as wildfires, storms, extreme heat events, floods, and droughts. Less obvious effects of climate change on health arise from changes to ecosystems that support the spread of disease, pathogens, or the distribution of contaminants to people, for example, the expansion of vector-borne diseases in new geographical regions, more water and air pollution due to warmer temperatures, or greater risks to food insecurity. Climate change is increasing vulnerability to multiple simultaneous hazards that threaten health (Mora et al., 2018), and continued global warming beyond 1.5°C increases risks of exceeding critical thresholds that would lead to more severe damage of natural systems and human societies (Haines & Ebi, 2019).

Health and social services play an important role in protecting Canadians from climate change impacts. They are the first lines of defence, whether through primary prevention (e.g., reducing GHG emissions in health care, reducing the urban heat island effect), secondary prevention (e.g., early warning systems, public education campaigns), or tertiary prevention (e.g., treating injuries and illnesses associated with climate-related hazards) (see Chapter 10: Adaptation and Health System Resilience). The failure of such services during an extreme event, or the diminished capacity to provide services over time, would have direct impacts on health and well-being. There is increasing recognition of the impacts that climate change can have on health systems (WHO, 2015; Balbus et al., 2016; Haines & Ebi, 2019), as evidenced by recent disasters such as Hurricanes Katrina and Sandy in the United States (Health Care without Harm, 2018) and catastrophic wildfires in Alberta and British Columbia (Purdy, 2016; Toews, 2018).

Certain populations in and outside Canada bear a disproportionate burden of the health impacts from climate change (Berry et al., 2014; Hoegh-Guldberg et al., 2018; Shultz et al., 2020) (see Chapter 2: Climate Change and Indigenous Peoples’ Health in Canada; Chapter 9: Climate Change and Health Equity). Globally, it has been estimated that children bear 88% of the burden of disease from climate change (WHO & UNEP, 2010). Climate change is a threat to the health of people in all countries. Some dynamics that drive risks, such as infectious diseases, effects on water and food systems, or supply chain disruptions, can transcend borders (Balbus et al., 2016; Friel, 2019), thereby affecting Canadians.

Climate change is increasing the risk of humanitarian crises (Jochum et al., 2018) and threatening the global health gains achieved over the past century (Smith et al., 2014). From 2014 and 2017, climate shocks were partly responsible for the increase in food-insecure people in the world to more than 800 million — a growth of between 37 million and 122 million (GCA, 2019). Globally, it has been estimated that 200 million people every year by 2050 could need international humanitarian aid because of the impacts of climate change, which is almost double the number of people (108 million) that required assistance in 2018 to recover from floods, storms, and wildfires (IFRCRCS, 2019). Possible linkages exist between climate-related hazards and human migration (UNHCR, 2015; Haines & Ebi, 2019; McLeman, 2020) — for example, the 2018 droughts in Central America coincided with international migration patterns (CRED, 2019). Impacts have also been linked with conflict (Schleussner et al., 2016; Werrell & Femia, 2017) — for example, droughts in Ethiopia have been indirectly linked to decreased food security and areas of conflict (WHO, 2018) and the 2006 drought in Syria contributed to the deterioration of economic conditions and subsequent conflict (Gleick, 2014; Kelley et al., 2015).

Climate change is considered a “threat multiplier” (Hallegatte et al., 2015) and is expected to lead to increased poverty, dislocation, and forced migration among many populations (Hoegh-Guldberg et al., 2018). It is also recognized as an increasingly important national health security issue, given the potential interplay between climate change and infectious diseases (Hawa, 2017) (see Chapter 6: Infectious Diseases). However, the way in which climate change shocks and stresses can compound other drivers of conflict and migration is complex, as are implications for human health, and research in these areas is still emerging (Hsiang, 2013; Bowles et al., 2015).

Impacts on the health of populations and communities may be immediate or may last years (e.g., non-communicable diseases such as mental health; see Chapter 4: Mental Health and Well-Being); they may also be long-lived, multi-generational, or irreversible, such as impacts on or the loss of cultures (WHO, 2018) (see Chapter 2: Climate Change and Indigenous Peoples’ Health in Canada). In addition, researchers are starting to link specific events that have affected health directly to climate change. For instance, specific extreme weather events, including the hot and dry conditions that contributed to record wildfires in British Columbia in 2016, or the record heat wave in that province in June, 2021 have been attributed to climate change (Herring et al., 2018; World Weather Attribution, 2021), allowing researchers to also make linkages to the health impacts of such events (Ebi et al., 2017; Hoegh-Guldberg et al., 2018). In addition, Vicedo-Cabrera et al. (2021) estimate that, between 1991 and 2018, 38.5% of heat-related mortality in 25 census metropolitan areas in Canada could be attributed to human-induced climate change.

Scientists are also learning more about the very large short-term and longer-term health co-benefits of well-designed GHG mitigation measures and of proactive adaptation actions in other sectors. Actions to address climate change in the agriculture, water and sanitation, infrastructure, energy, urban design, and transportation sectors, for example, can reduce environmental pollution and support healthy lifestyles and communities (Haines et al., 2009; Smith et al., 2014; Martinez et al., 2018). The potential benefits, for example, of reduced deaths from air pollution, are so large that the Lancet Commission on Climate and Health has called climate change the “greatest global health opportunity of the 21st Century” (Watts et al., 2015, p.1) (see Chapter 5: Air Quality). Research suggests that, for a range of future scenarios, the value of the benefits to health resulting from policies and activities in line with meeting the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change Paris Agreement targets could exceed their costs (Markandya et al., 2018). Canada is a signatory to the Paris Agreement and has pledged to reduce its GHG emissions to 511 Mt CO2 equivalent by 2030 and to achieve a net-zero-emissions economy by 2050 (Government of Canada, 2021).

Health system infrastructure and services in Canada are being affected by climate-related hazards; reduced pressures and costs to health systems from improved population health through such measures can free up resources to build climate-resilient health systems and recover from the unavoidable impacts (Martinez et al., 2018). Greater understanding of how to gauge the climate resilience of health systems (e.g., indicators), tools to facilitate needed adaptation, and roles and responsibilities of key actors and partnership opportunities will support preparedness efforts (see Chapter 10: Adaptation and Health System Resilience).