1.1

Introduction

In 2014, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) stated that “warming of the climate system is unequivocal” (IPCC, 2014). Since then, evidence of change has continued to build, with observed increases in temperature (over land and oceans), rising sea levels, loss of snow and ice, and shifting precipitation patterns at the global scale (e.g., IPCC, 2018; 2019; USGCRP, 2018). Many of the changes brought about by increases in temperature are unprecedented, and most are projected to persist and intensify over the current century (Bush et al., 2019; IPCC, 2014). A clearer picture of the impacts is also emerging, with recognition that climate change has the potential to affect almost every aspect of our lives—our health and well-being, economies, environment, and even our identities and sense of self. It is also increasingly clear that the impacts are not evenly distributed, and that certain regions, populations and groups are being disproportionately affected.

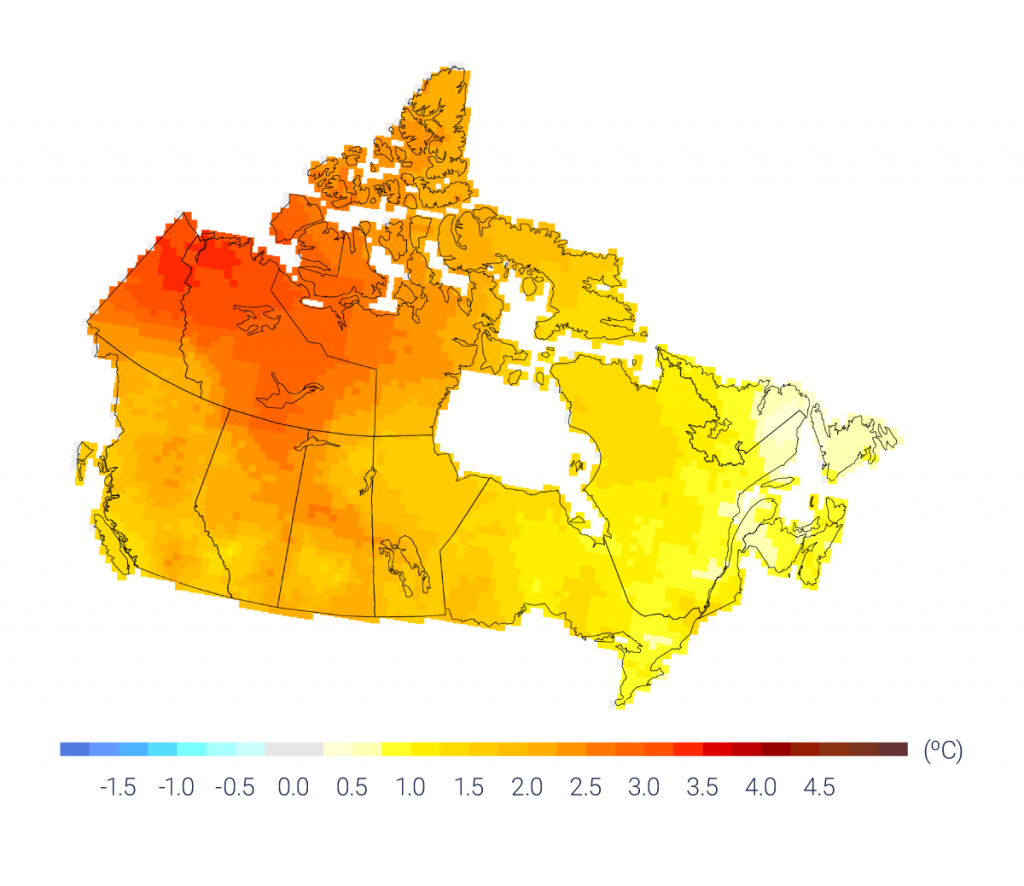

We are also seeing these trends in Canada. Observed warming in Canada is, on average, approximately double the magnitude of global warming (Bush and Lemmen, 2019), with northern parts of the country experiencing the greatest rates of change (see Figure 1.1). We are experiencing more extreme heat, less extreme cold, longer growing seasons, shorter snow and ice cover seasons, earlier spring peak streamflow, thinning glaciers, thawing permafrost and rising sea levels (Bush and Lemmen, 2019). Losses from extreme events, such as floods and wildfires, are also increasing. In recent Canadian surveys, 87% of respondents indicated that they are already seeing the effects of climate change in their community (Natural Resources Canada, 2019), and 93% indicated that they believe climate change is either having an impact on their health now or will in the future (Environics Research Group, 2017).

Figure 1.1

-

Figure 1.1

Map showing observed changes in annual temperature (°C) across Canada between 1948 and 2016.

Source

Zhang et al., 2019.

These observed trends and documented impacts have firmly established the scientific basis for climate change. Debates over whether climate change is real have largely been replaced by discussions on how to respond. The need to plan for and to address climate change impacts grows daily. Decisions taken now to address climate change impacts will have important ongoing implications for Canada’s society, economy and environment. However, while there is clearly an urgent need to take action on climate change (IPCC, 2018), the path forward can be complicated. Climate change is a global issue with widespread, pervasive, interacting and often complex impacts occurring at all scales. At a basic level, there are two critically important response pathways—mitigation (greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions reduction) and adaptation—which are related and co-dependent (see Box 1.1).

This report focuses on climate change adaptation—actions that reduce the negative impacts of climate change or that take advantage of potential new opportunities. Adaptation builds resilience and reduces risk related to current and future climate change impacts. It involves adjusting plans, policies and actions, and can be reactive (i.e., occurring in response to climate change impacts) or anticipatory (i.e., occurring before impacts of climate change are observed). As a concept, adaptation is straightforward; in practice, however, it can range from being simple to incredibly complex. Our understanding of the ways in which climate change affects vulnerable groups and segments of the population is continuing to develop, highlighting the important socioeconomic and equity dimensions of adaptation decisions. Adaptation also offers the opportunity to generate significant co-benefits, such that investments to address climate change impacts in one particular sector or area can result in benefits elsewhere. Similarly, unintended consequences can result if planning and decisions do not adequately consider the broad system and context in which the decisions are being made.

To help address complexities and promote action on climate change adaptation, decision makers need access to reliable information. Knowledge assessments on climate change impacts and adaptation address this need by providing decision makers with the foundation necessary for making evidence-based decisions. Such assessments synthesize existing knowledge on the key issues by following a rigorous process that ensures the end products are credible, relevant and useful to decision makers. While being policy-relevant and structured to inform decisions, assessments are not policy-prescriptive, nor do they provide specific instructions or recommendations. Assessments can be carried out at different scales—from the international assessments of the IPCC to national, regional and local-scale initiatives. Knowledge assessments differ from risk assessments, which apply analytical methods to estimate the probability and consequence of risks associated with current and future climate change impacts. However, risk assessments can both inform and be informed by knowledge assessments. Recent examples of risk assessments in Canada include those at the national scale (e.g., CCA, 2019) and regional scale (e.g., Ministry of Environment and Climate Change Strategy, 2019).