Adler, D. (2018). Turning the Tide in Coastal and Riverine Energy Infrastructure Adaptation: Can an Emerging Wave of Litigation Advance Preparation for Climate Change. Oil & Gas, Natural Resources, and Energy Journal, 4(4), 519. Retrieved July 2020, from <https://digitalcommons.law.ou.edu/onej/vol4/iss4/2>

Adriano, L. (2019). Study: Canadian flood mapping information is “inadequate, incomplete, hard to locate”. Insurance Business Canada. Retrieved July 2020, from <https://www.insurancebusinessmag.com/ca/news/flood/study-canadian-flood-mapping-information-is-inadequate-incomplete-hard-to-locate-160498.aspx>

Anderson, N. (2019). IFRS Standards and climate-related disclosures. IFRS. Retrieved July 2020, from <https://cdn.ifrs.org/-/media/feature/news/2019/november/in-brief-climate-change-nick-anderson.pdf?la=en>

Anderson v. Manitoba, 2017 MBCA 14, 2017 CarswellMan 31, [2017] 4 W.W.R. 702, 275 A.C.W.S. (3d) 38, 35 C.C.L.T. (4th) 205, 408 D.L.R. (4th) 329, 98 C.P.C. (7th) 222 (Manitoba Court of Appeal).

Australian Sustainable Finance Initiative (2019). Developing an Australian Sustainable Finance Roadmap: Progress Report. Retrieved July 2020, from <https://www.sustainablefinance.org.au/s/ASFI-Progress-Report-Final.pdf>

Bank of Montreal. (2019a). Sustainable Financing Framework. Retrieved July 2020, from <https://www.bmo.com/ir/files/F19%20Files/BMOSustainableFinancingFramework.pdf>

Bank of Montreal. (2019b). BMO Issues Inaugural Sustainability Bond. Retrieved July 2020, from <https://newsroom.bmo.com/2019-10-21-BMO-Issues-Inaugural-Sustainability-Bond>

Barnes v. Edison International, 2:18-cv-09690 (C.D. Cal.). Retrieved July 2020, from <http://climatecasechart/case/barnes-v-edison-international>

Bednar, D., Henstra, D., and McBean, G. (2019). The governance of climate change adaptation: are networks to blame for the implementation deficit? Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning, 21(6), 702-717. Retrieved July 2020, from <https://doi.org/10.1080/1523908X.2019.1670050>

Bednar, D., Raikes, J., and McBean, G. (2018). The governance of climate change adaptation in Canada. Toronto: Institute for Catastrophic Loss Reduction. Retrieved July 2020, from <https://www.iclr.org/images/CCA_Climate_change_report_2018.pdf>

Bennett, V. (2019). World’s first dedicated climate resilience bond, for US$ 700m, is issued by EBRD. European Bank for Reconstruction and Development. Retrieved July 2020, from <https://www.ebrd.com/news/2019/worlds-first-dedicated-climate-resilience-bond-for-us-700m-is-issued-by-ebrd-.html>

Bishop v. Regional Municipality of Durham, 2007 CarswellOnt 10163 (Ontario Superior Court of Justice).

Blewett, T. (2019, April 27). ‘People will lose a lot:’ Gatineau fighting floods alongside other Quebec communities. Ottawa Citizen. Retrieved July 2020, from <https://ottawacitizen.com/news/local-news/people-will-lose-a-lot-gatineau-fighting-floods-alongside-other-quebec-communities/>

Buberl, T. (2017). Unsustainable business is un-investable and uninsurable business. One Planet Summit, Axa CEO Speech. Retrieved July 2020, from <https://www-axa-com.cdn.axa-contento-118412.eu/www-axa-com%2Ff5520897-b5a6-40f3-90bd-d5b1bf7f271b_climatesummit_ceospeech_va.pdf>

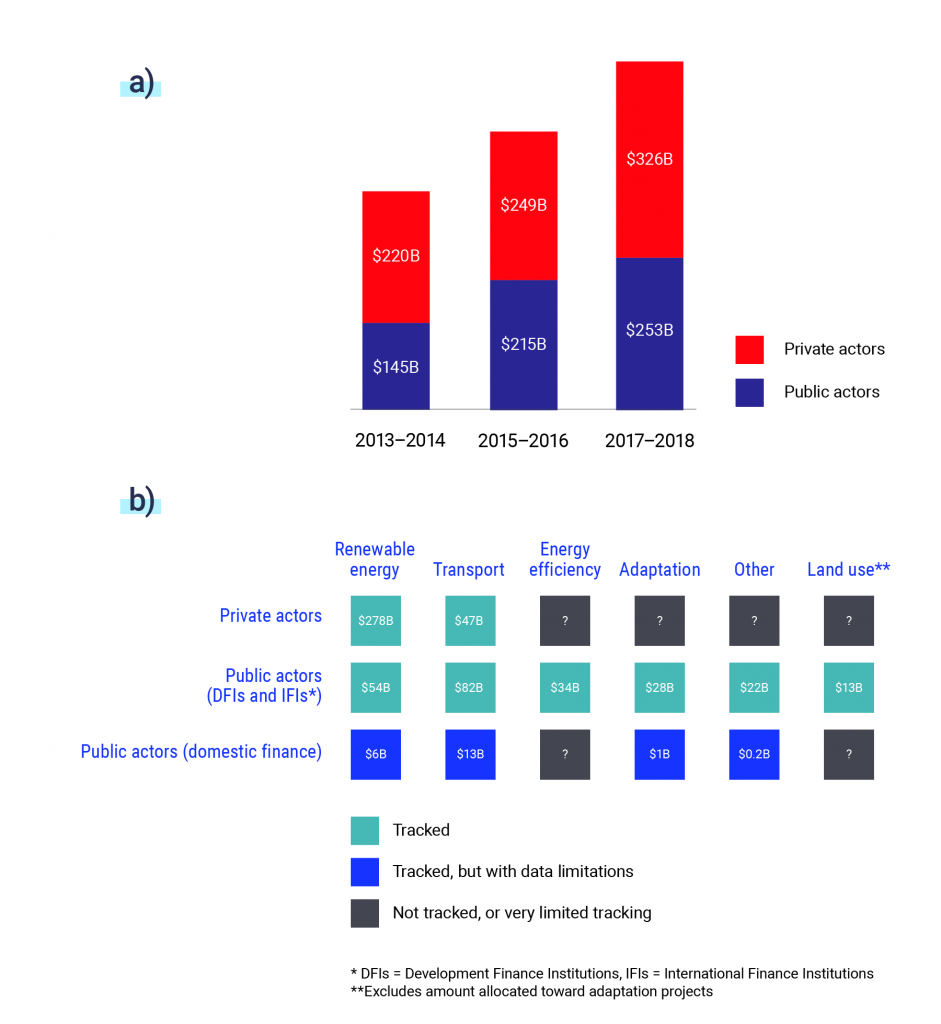

Buchner, B., Clark, A., Falconer, A., Macquarie, R., Meattle, C., Tolentino, R. and Wetherbee, C. (2019). Global Landscape of Climate Finance 2019. London: Climate Policy Initiative. Retrieved July 2020, from <https://climatepolicyinitiative.org/publication/global-landscape-of-climate-finance-2019/>

Burger, M., Wentz, J., and Horton, R. (2020). The Law and Science of Climate Change Attribution. Columbia Journal of Environmental Law, 45(1). Retrieved July 2020, from <https://doi.org/10.7916/cjel.v45i1.4730>

Burns Bog Conservation Society v. Canada, 2012 CarswellNat 3188, 2012 CarswellNat 4657, 2012 FC 1024, 2012 CF 1024, [2012] F.C.J. No. 1110, 221 A.C.W.S. (3d) 356, 417 F.T.R. 98 (Eng.), 71 C.E.L.R. (3d) 118 (Federal Court).

Bush, E. and Lemmen, D. (Eds.) (2019). Canada’s Changing Climate Report. Ottawa: Government of Canada. Retrieved July 2020, from <https://changingclimate.ca/CCCR2019/>

Cambridge Institute for Sustainability Leadership (2019a). Physical risk framework: Understanding the impacts of climate change on real estate lending and investment portfolios. Retrieved July 2020, from <https://www.cisl.cam.ac.uk/resources/publication-pdfs/cisl-climate-wise-physical-risk-framework-report.pdf>

Cambridge Institute for Sustainability Leadership (2019b). Transition risk framework: Managing the impacts of the low carbon transition on infrastructure investments. Retrieved July 2020, from <https://www.cisl.cam.ac.uk/resources/publication-pdfs/cisl-climate-wise-transition-risk-framework-report.pdf>

Canada Enterprise Emergency Funding Corporation (2020). Large employer emergency financing facility factsheet. Retrieved July 2020, from <https://www.cdev.gc.ca/leeff-factsheet/>

Canada Infrastructure Bank (n.d.). About Us. Retrieved September 2020, from <https://cib-bic.ca/en/about-us/>

Canada Infrastructure Bank (2020). Prime Minister announces infrastructure plan to create jobs and grow the economy. Retrieved July 2020, from <https://cib-bic.ca/en/the-canada-infrastructure-bank-announces-a-plan-to-create-jobs-and-grow-the-economy/>

Canadian Infrastructure Report Card (2019). Monitoring the State of Canada’s Core Public Infrastructure: The Canadian Infrastructure Report Card 2019. Retrieved July 2020, from <http://canadianinfrastructure.ca/downloads/canadian-infrastructure-report-card-2019.pdf>

Canadian Institute for Climate Choices (2020). Charting Our Course: Bringing clarity to Canada’s climate policy choices on the journey to 2050. Retrieved July 2020, from <https://climatechoices.ca/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/FINAL_Charting-Our-Course.pdf>

Canadian Intergovernmental Conference Secretariat (2018). NEWS RELEASE – Federal/Provincial/Territorial Ministers met to Discuss Emergency Management. Retrieved July 2020, from <https://scics.ca/en/product-produit/news-release-federal-provincial-territorial-ministers-met-to-discuss-emergency-management/>

Canadian Securities Administrators (2010). CSA Staff Notice 51-333: Environment Reporting Guidance. Retrieved July 2020, from <https://www.osc.gov.on.ca/documents/en/Securities-Category5/csa_20101027_51-333_environmental-reporting.pdf>

Canadian Securities Administrators (2018). CSA Staff Notice 51-354: Report on Climate change-related Disclosure Project. Retrieved July 2020, from <https://www.osc.gov.on.ca/en/SecuritiesLaw_csa_20180405_51-354_disclosure-project.htm>

Canadian Securities Administrators (2019). CSA Staff Notice 51-358: Reporting of Climate Change-related Risks. Retrieved July 2020 from <https://www.osc.gov.on.ca/documents/en/Securities-Category5/csa_20190801_51-358_reporting-of-climate-change-related-risks.pdf>

Canadian Water Network and Insurance Bureau of Canada (2019). Improving Flood Risk Evaluation through Cross-Sector Sharing of Richer Data. Retrieved July 2020, from <http://cwn-rce.ca/wp-content/uploads/CWN-IBC-Improving-Flood-Risk-Evaluation.pdf>

Carney, M. (2019). A New Horizon. Retrieved from Bank of England: <https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/speech/2019/mark-carney-speech-at-european-commission-high-level-conference-brussels>

CatIQ (n.d.). Retrieved September, 2020 from: <www.catiq.com>

CBC News (2019). High River wants to buy flood homes back from the province. Retrieved July 2020, from <https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/calgary/high-river-homes-flood-mitigation-buy-back-1.4972863>

CCA [Council of Canadian Academies] (2019). Canada’s Top Climate Change Risks. Ottawa: The Expert Panel on Climate Change Risks and Adaptation Potential, Council of Canadian Academies. Retrieved July 2020, from <https://cca-reports.ca/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/Report-Canada-top-climate-change-risks.pdf>

CDP (2020). What we do. Retrieved September 2020, from <https://www.cdp.net/en/info/about-us/what-we-do>

Circé, M., Da Silva, L., Boyer-Villemaire, U., Duff, G., Desjarlais, C. and Morneau, F. (2016). Cost-Benefit Analysis for Adaptation Option in Quebec’s Coastal Areas – Synthesis Report. Montréal: Ouranos. Retrieved July 2020, from <https://www.ouranos.ca/publication-scientifique/Synthesis-Report-Qc.pdf>

City of Ottawa (n.d.). Investor Relations. Retrieved April 2020, from <https://ottawa.ca/en/business/doing-business-city/investor-relations#green-bonds>

City of Vancouver (2018). City of Vancouver – Green Bond Program. Retrieved July 2020, from <https://vancouver.ca/your-government/investor-relations.aspx>

Climate Accountability Institute (2019). Carbon Majors: Update of top twenty companies 1965–2017. Retrieved July 2020, from <http://climateaccountability.org/pdf/CAI%20PressRelease%20OA%20Dec19c.pdf>

Climate Action 100+ (2019). 2019 Progress Report. Retrieved July 2020, from <https://climateaction100.files.wordpress.com/2019/10/progressreport2019.pdf>

Climate Bonds Initiative (2019). Green bonds: The state of the market 2018. Retrieved July 2020, from <https://www.climatebonds.net/resources/reports/green-bonds-state-market-2018>

Climate Bonds Initiative (2020). Explaining Green Bonds. Retrieved July 2020, from <https://www.climatebonds.net/market/explaining-green-bonds>

Cooper v. Hobart, Cooper v. Hobart, 2001 CarswellBC 2502, 2001 CarswellBC 2503, 2001 SCC 79, 2001 CSC 79, [2001] 3 S.C.R. 537, [2001] B.C.W.L.D. 1084, [2001] S.C.J. No. 76, [2001] B.C.T.C. 215, [2002] 1 W.W.R. 221, 110 A.C.W.S. (3d) 943, 160 B.C.A.C. 268, 206 D.L.R. (4th) (Supreme Court of Canada).

Corporate Knights and the Council for Clean Capitalism (2018). Clean Financing for Heavy Industry. Retrieved July 2020, from <https://www.corporateknights.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/Clean-Transition-Project-Categories-Draft.pdf>

CPA [Chartered Professional Accountants] Canada (2019a). Progressive Investors and Corporate Disclosure – The Unstoppable Transition to a Resilient, Low Carbon Economy. Toronto. Retrieved July 2020, from <https://www.cpacanada.ca/-/media/site/operational/rg-research-guidance-and-support/docs/02097-rg-progressive-investors-corporate-disclosure-interviews-april-2019.pdf?la=en&hash=C5C6377D4F6DD33EE11E07CDEB8778CCB1B4C2F5>

CPA [Chartered Professional Accountants] (2019b). Climate-Related Reporting in the Mining Sector. Retrieved July 2020, from <https://www.cpacanada.ca/en/business-and-accounting-resources/financial-and-non-financial-reporting/sustainability-environmental-and-social-reporting/publications/climate-related-reporting-in-the-mining-sector>

CPA [Chartered Professional Accountants] (2019c). Climate-Related Reporting in the Energy Sector. Retrieved July 2020, from <https://www.cpacanada.ca/en/business-and-accounting-resources/financial-and-non-financial-reporting/sustainability-environmental-and-social-reporting/publications/climate-related-reporting-in-the-energy-sector>

CPA [Chartered Professional Accountants] (2019d). Enhancing Climate-related Disclosure by Cities: A Guide to Adopting the Recommendations of the Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures (TCFD). Retrieved July 2020, from <https://www.cpacanada.ca/en/business-and-accounting-resources/financial-and-non-financial-reporting/sustainability-environmental-and-social-reporting/publications/tcfd-guide-for-cities>

CPA [Chartered Professional Accountants] (2020). Summary Report: Study of Climate-related Disclosure by Canadian Public Companies. Retrieved July 2020, from <https://www.cpacanada.ca/-/media/site/operational/rg-research-guidance-and-support/docs/02370-rg-study-climate-related-disclosures-summary-report-feb-2020.pdf>

Crown Liability and Proceedings Act, 2019, SO 2019, c 7, Sch 17. Retrieved February 2021, from <https://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/eng/acts/c-50/>

Canadian Standards Authority Group (2020). Defining Green & Transition Finance in Canada. Retrieved March 2020, from <https://www.csagroup.org/news/defining-green-transition-finance-in-canada/>

Czajkowski, J., Simmons, K. M. and Done, J. M. (2017). Demonstrating the Intensive Benefit to the Local Implementation of a Statewide Building Code. Risk Management and Insurance Review, 20(3), 363-390. Retireved July 2020, from <https://doi.org/10.1111/rmir.12086>

Department of Finance Canada (2019). Backgrounder: Transition to a Clean Economy. Government of Canada, Ottawa, ON. Retrieved July 2020, from <https://www.canada.ca/en/department-finance/news/2019/06/backgrounder-transition-to-a-clean-economy.html>

Ekwurzel, B., Boneham, J., Dalton, M. W., Heede, R., Mera, R. J., Allen, M. R. and Frumhoff, P. C. (2017). The rise in global atmospheric CO2, surface temperature, and sea level from emissions traced to major carbon producers. Climate Change, 144(4), 579-590. Retrieved July 2020, from <https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-017-1978-0>

Environnement Jeunesse c. Procureur général du Canada, 2019 CarswellQue 6311, 2019 QCCS 2885, 29 C.E.L.R. (4th) 313, 308 A.C.W.S. (3d) 775, EYB 2019-313892 (Cour supérieure du Québec). Retrieved July 2020, from http://climatecasechart.com/non-us-case/environnement-jeunesse-v-canadian-government/

EU High-Level Expert Group on Sustainable Finance (2018). Final report 2018 by the High-Level Expert Group on Sustainable Finance. European Commission. Retrieved July 2020, from <https://ec.europa.eu/info/publications/180131-sustainable-finance-report_en>

EU Technical Expert Group on Sustainable Finance (2020). Taxonomy: Final report of the Technical Expert Group on Sustainable Finance. European Commission. Retrieved July 2020, from <https://ec.europa.eu/knowledge4policy/publication/sustainable-finance-teg-final-report-eu-taxonomy_en>

Evans, C. and Feltmate, B. (2019). Water on the Rise: Protecting Canadian Homes from the Growing Threat of Flooding. University of Waterloo, Intact Centre on Climate Adaptation. Retrieved July 2020, from <https://www.intactcentreclimateadaptation.ca/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/Home-Flood-Protection-Program-Report-1.pdf>

Expert Panel on Sustainable Finance (2018). Interim Report of the Expert Panel on Sustainable Finance. Gatineau: Environment and Climate Change Canada. Retrieved July 2020, from <http://publications.gc.ca/pub?id=9.863536&sl=0>

Expert Panel on Sustainable Finance (2019). Final Report of the Expert Panel on Sustainable Finance: Mobilizing Finance for Sustainable Growth. Gatineau: Environment and Climate Change Canada. Retrieved July 2020, from <https://www.canada.ca/en/environment-climate-change/services/climate-change/expert-panel-sustainable-finance.html>

Feltmate, B., Moudrak, N., Bakos, K. and Schofield, B. (2020). Factoring Climate Risk into Financial Valuation. University of Waterloo, Intact Centre on Climate Adaptation. Retrieved July 2020, from <https://www.intactcentreclimateadaptation.ca/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/Factoring-Climate-Risk-into-Financial-Valuation.pdf>

Flavelle, C. (2019, July 24). Moody’s Buys Climate Data Firm, Signaling New Scrutiny of Climate Risks. The New York Times. Retrieved July 2020, from <https://www.nytimes.com/2019/07/24/climate/moodys-ratings-climate-change-data.html>

Friends of the Earth v. Governor General in Council of Canada, 2008 FC 1183, 2008 CF 1183, 2008 CarswellNat 3763, 2008 CarswellNat 5075, [2008] F.C.J. No. 1464, [2009] 3 F.C.R. 201, 170 A.C.W.S. (3d) 438, 299 D.L.R. (4th) 583, 336 F.T.R. 117 (Eng.), 39 C.E.L.R. (3d) 191, 93 Admin. L.R. (4th) 18 (Federal Court).

Global Commission on Adaptation (2019). Adapt Now: a Global Call for Leadership on Climate Resilience. Retrieved July 2020, from <https://cdn.gca.org/assets/2019-09/GlobalCommission_Report_FINAL.pdf>

Goldstein, A., Turner, W., Gladstone, J., and Hole, D. (2019). The private sector’s climate change risk and adaptation blind spots. Nature Climate Change, 9, 18-25. Retrieved July 2020 from, <https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-018-0340-5>

Golnaraghi, M. (Ed.) (2012). Institutional Partnerships in Multi-Hazard Early Warning Systems: A Compilation of Seven National Good Practices and Guiding Principles. Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg. Retrieved July 2020, from <https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-25373-7>

Golnaraghi, M. (2019a). Opinion: From “fragmented” trends to new “integrated” business models. Retrieved July 2020, from <https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/opinion-from-fragmented-trends-new-integrated-models-maryam/>

Golnaraghi, M. (2019b). Advancements in Modelling and Integration of Physical and Transition Climate Risk Core insurance business, asset management and investment applications: Background Paper prepared for the Geneva Association 2019 Climate Change Forum. Zurich: The Geneva Association. Retrieved July 2020, from <https://www.genevaassociation.org/sites/default/files/background_paper_for_2019_eecr_forum_final_08.07.2019.pdf>

Government of Canada (2016). Pan-Canadian Framework on Clean Growth and Climate Change. Retrieved July 2020, from <https://www.canada.ca/en/services/environment/weather/climatechange/pan-canadian-framework/climate-change-plan.html>

Government of Canada (2020). Canadian Climate Data and Scenarios. Retrieved September 2020, from <http://climate-scenarios.canada.ca/?page=main>

Grantham Research Institute on Climate Change and the Environment (2020). Climate Change Laws of the World. London School of Economics. Retrieved September 2020, from <https://climate-laws.org/>

Green Finance Taskforce (2018). A report to Government by the Green Finance Taskforce: Accelerating Green Finance. Prepared for the Government of the United Kingdom. Retrieved July 2020, from <https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/accelerating-green-finance-green-finance-taskforce-report>

Greenpeace Canada v. Minister of the Environment, Conservation and Parks, 2019 ONSC 5629, 2019 CarswellOnt 16447, 148 O.R. (3d) 191, 28 C.E.L.R. (4th) 132, 310 A.C.W.S. (3d) 533, 439 D.L.R. (4th) 345 (Ontario Superior Court of Justice).

Greenpeace Southeast Asia and Others (Philippines Commission on Human Rights). Retrieved July 2020, from <http://climatecasechart.com/non-us-case/in-re-greenpeace-southeast-asia/>

Grzadkowska, A. (2019). Commercial properties being submerged by rising flood risk. Insurance Business Canada. Retrieved July 2020, from <https://www.insurancebusinessmag.com/ca/news/catastrophe/commercial-properties-being-submerged-by-rising-flood-risk-192065.aspx>

Guilbault, S., Kovacs, P., Berry, P. and Richardson, G. R. (Eds.) (2016). Cities Adapt to Extreme Heat: Celebrating Local Leadership. Institute for Catastrophic Loss Reduction. Retrieved July 2020, from <https://www.iclr.org/wp-content/uploads/PDFS/cities-adapt-to-extreme-heat.pdf>

Gundlach, J. and Klein, J. (2018). The Built Environment, Chapter 6 in Climate Change, Public Health and the Law, (Eds.) M. Burger and J. Gundlach. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Retrieved July 2020, from <https://doi.org/10.1017/9781108278010.007>

Harford, D. and Raftis, C. (2019). Low Carbon Resilience: Best Practices for Professionals. Simon Frasier University, Adaptation to Climate Change Team. Retrieved July 2020, from <https://www.weadapt.org/system/files_force/lcr_best_practices_final.pdf>

Heede, R. (2014). Tracing anthropogenic carbon dioxide and methane emissions to fossil fuel and cement producers, 1854-2010. Climatic Change, 122(1–2), 229–241. Retrieved July 2020, from <https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-013-0986-y>

Henstra, D. and Thistlethwaite, J. (2017). Flood Risk Management: What Is the Role Ahead for the Government of Canada? Centre for International Governance Innovation Policy Brief No. 103. Retrieved July 2020, from <https://www.cigionline.org/sites/default/files/documents/Policy%20Brief%20No.103_0.pdf>

Hogg, P. (2007). Constitutional Law of Canada, 5th ed. Scarborough: Thomson Carswell.

IBC [Insurance Bureau of Canada] (2015). A Primer on Financial Risk from Natural Disasters: The Case for Public-Private Collaboration. Retrieved July 2020, from <http://assets.ibc.ca/Documents/Resources/2015_PubPrivPart.pdf>

IBC [Insurance Bureau of Canada] (2019a). Investing in Canada’s Future: The Cost of Climate Adaptation. Retrieved July 2020, from <http://assets.ibc.ca/Documents/Disaster/The-Cost-of-Climate-Adaptation-Summary-EN.pdf>

IBC [Insurance Bureau of Canada] (2019b). Options for Managing Flood Costs of Canada’s Highest Risk Residential Properties: A Report of the National Working Group on Financial Risk of Flooding. Retrieved July 2020, from <http://assets.ibc.ca/Documents/Studies/IBC-Flood-Options-Paper-EN.pdf>

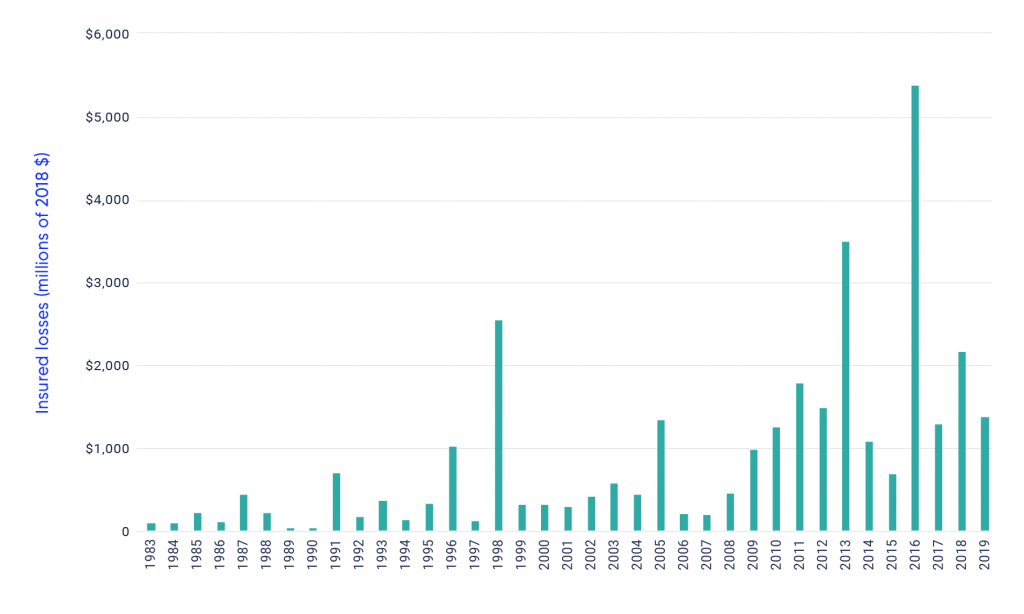

IBC [Insurance Bureau of Canada] (2020). Canada’s P&C insurance industry, all sectors, Section 1 in 2020 Facts of the Property and Casualty Insurance Industry in Canada. Retrieved July 2020, from <http://assets.ibc.ca/Documents/Facts%20Book/Facts_Book/2020/IBC-2020-Facts-section-one.pdf>

ICCA [Intact Centre on Climate Adaptation] (n.d.). Flood Protection Training. Retrieved April 2020, from <https://www.intactcentreclimateadaptation.ca/programs/home_flood_protect/training/>

Infrastructure Canada (2018). Government of Canada launches new fund to help reduce the impacts of climate change and better protect Canadians against natural disasters. Government of Canada. Retrieved July 2020, from <https://www.canada.ca/en/office-infrastructure/news/2018/05/government-of-canada-launches-new-fund-to-help-reduce-the-impacts-of-climate-change-and-better-protect-canadians-against-natural-disasters.html>

Infrastructure Canada (2019). Climate Lens – General Guidance. Government of Canada. Retrieved July 2020, from <https://www.infrastructure.gc.ca/pub/other-autre/cl-occ-eng.html>

Insurance Institute of Canada (2020). Climate Risks: Implications for the Insurance Industry in Canada. Retrieved July 2020, from <https://www.insuranceinstitute.ca/-/media/CIP-Society/2020-Climate-Risks-Report/IIC-2020-ClimateRisks-Report.pdf?la=en&hash=B84E383B69341AD4C99FC186122AD789649DA2AF>

IPCC [Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change] (2019). Global Warming of 1.5°C. An IPCC Special Report on the impacts of global warming of 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels and related global greenhouse gas emission pathways, in the context of strengthening the global response to the threat of climate change, sustainable development, and efforts to eradicate poverty. (Eds.) Masson-Delmotte, V., P. Zhai, H.-O. Pörtner, D. Roberts, J. Skea, P.R. Shukla, A. Pirani, W. Moufouma-Okia, C. Péan, R. Pidcock, S. Connors, J.B.R. Matthews, Y. Chen, X. Zhou, M.I. Gomis, E. Lonnoy, T. Maycock, M. Tignor, and T. Waterfield. World Meteorological Organization, Geneva, Switzerland. Retrieved July 2020, from <https://www.ipcc.ch/sr15/>

Kovacs, P., Guilbault, S., and Sandink, D. (2014). Cities Adapt to Extreme Rainfall: Celebrating Local Leadership. Toronto: Institute for Catastrophic Loss Reduction. Retrieved July 2020, from <https://www.iclr.org/wp-content/uploads/PDFS/CITIES_ADAPT_DIGITAL_VERSION.compressed.pdf>

Kovacs, P., Guilbault, S., Darwish, L., and Comella, M. (2018). Cities Adapt to Extreme Weather: Celebrating Local Leadership. Toronto: Institute for Catastrophic Loss Reduction. Retrieved July 2020, from <https://www.iclr.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/cities-adapt-to-extreme-weater-update-website.pdf>

KPMG (2015). Demystifying the Public Private Partnership Paradigm: The Nexus between Insurance, Sustainability and Growth. Retrieved July 2020, from <https://home.kpmg/content/dam/kpmg/pdf/2015/06/public-private-partnerships.pdf>

Kunreuther, H. (2015). The Role of Insurance in Reducing Losses from Extreme Events: The Need for Public-Private Partnerships. The Geneva Papers on Risk and Insurance: Issues and Practice, 40(4), 741‒762. Retrieved July 2020, from <https://link.springer.com/article/10.1057/gpp.2015.14>

La Rose et al. v. Her Majesty the Queen. Retrieved July 2020, from <http://climatecasechart.com/non-us-case/la-rose-v-her-majesty-the-queen/>

LAMPS (2020). Ontario Climate Data Portal. York University. Retrieved September 2020, from <http://lamps.math.yorku.ca/OntarioClimate/>

Lau, R. (2019, November 18). 2019 floods: Quebec wants to standardize flood regulations for towns in the Laurentians. CTV News. Retrieved July 2020, from <https://montreal.ctvnews.ca/2019-floods-quebec-wants-to-standardize-flood-regulations-for-towns-in-the-laurentians-1.4690871>

Laukkonen, J., Kim-Blanco, P., Lenhart, J., Keiner, M., Cavric, B. and Njenga, C. (2009). Combining Climate Change Adaptation and Mitigation Measures. Habitat International, 33(3), 287–292. Retrieved July 2020, from <https://doi.org/10.1016/j.habitatint.2008.10.003>

Leghari v. Federation of Pakistan, W.P. No. 25501/2015 (Lahore High Court). Retrieved July 2020, from <http://climatecasechart.com/non-us-case/ashgar-leghari-v-federation-of-pakistan/>

Lho’imggin et al. v. Her Majesty the Queen. Retrieved July 2020, from <http://climatecasechart.com/non-us-case/gagnon-et-al-v-her-majesty-the-queen/>

Linden, A. and Feldthusen, B. (2007). Halsbury’s Laws of Canada: Negligence. Markham: LexisNexis.

Lliuya v. RWE AG, 2 O 285/15 (District Court Essen). Retrieved July 2020, from <http://climatecasechart.com/non-us-case/lliuya-v-RWE/>

Local Government Act, RSBC 2015 c.1 (2015).

Mahony, D. (Ed.). (2014). The Law of Climate Change in Canada. Toronto: Carswell.

Marjanac, S. and Patton, L. (2018). Extreme weather event attribution science and climate change litigation: an essential step in the causal chain? Journal of Energy & Natural Resources Law, 36(3), 265–298. Retrieved July 2020, from <https://doi.org/10.1080/02646811.2018.1451020>

Mathur et al. v. Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Ontario. Retrieved July 2020, from <http://climatecasechart.com/non-us-case/mathur-et-al-v-her-majesty-the-queen-in-right-of-ontario/>

Ministère des Finances du Québec (n.d.). Québec Green Bond Framework. Retrieved April 2020, from <http://www.finances.gouv.qc.ca/documents/Autres/en/AUTEN_Green_Bond_Framework.pdf>

Moran, D. and Mihaly, E. (2018). Climate Adaptation and Liabiliity: A Legal Primer and Workshop Summary Report. Retrieved July 2020, from <https://www.clf.org/wp-content//uploads/2018/01/GRC_CLF_Report_R8.pdf>

Moudrak, N. and Feltmate, B. (2017). Preventing Disaster Before It Strikes: Developing a Canadian Standard For New Flood-Resilient Residential Communities. University of Waterloo, Intact Centre on Climate Adaptation. Retrieved July 2020, from <http://www.intactcentreclimateadaptation.ca/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/Preventing-Disaster-Before-It-Strikes.pdf>

Moudrak, N. and Feltmate, B. (2019a). Weathering the Storm: Developing a Canadian Standard for Flood-Resilient Existing Communities. University of Waterloo, Intact Centre on Climate Adaptation. Retrieved July 2020, from <https://www.intactcentreclimateadaptation.ca/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/Weathering-the-Storm.pdf>

Moudrak, N. and Feltmate, B. (2019b). Ahead of the Storm: Developing Flood-Resilience Guidance for Canada’s Commercial Real Estate. University of Waterloo, Intact Centre on Climate Adaptation. Retrieved July 2020, from <https://www.intactcentreclimateadaptation.ca/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/Ahead-of-the-Storm-1.pdf>

Moudrak, N., Feltmate, B., Venema, H., and Osman, H. (2018). Combating Canada’s Rising Flood Costs: Natural infrastructure is an underutilized option. University of Waterloo, Intact Centre on Climate Adaptation, Waterloo (ON). Retrieved July 2020, from <https://www.intactcentreclimateadaptation.ca/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/IBC_Wetlands-Report-2018_FINAL.pdf>

Multihazard Mitigation Council and Council on Finance, Insurance and Real Estate (2015). Developing Pre-Disaster Resilience Based on Public and Private Incentivization. National Institute of Building Sciences. Retrieved July 2020, from <http://c.ymcdn.com/sites/www.nibs.org/resource/resmgr/MMC/MMC_ResilienceIncentivesWP.pdf>

National Bank of Canada (2018). Sustainability Bond Framework. Retrieved July 2020, from <https://www.nbc.ca/content/dam/bnc/a-propos-de-nous/relations-investisseurs/fonds-propres-et-dette/nbc-sustainability-bond-framework.pdf>

National Bank of Canada (2019). National Bank of Canada is the first North American bank to issue a USD Sustainability Bond on the international stage. Retrieved July 2020, from <https://www.nbc.ca/en/about-us/news/news-room/press-releases/2019/20191002-Banque-Nationale-annonce-premiere-emission-obligations-durables-dollars-US-par-une-banque-nord-americaine-a-international.html>

Network for Greening the Financial System (2020). Annual Report 2019. Retrieved July 2020, from <https://www.ngfs.net/sites/default/files/medias/documents/ngfs_annual_report_2019.pdf>

Office of the Superintendent of Financial Institutions (2013). Earthquake Exposure Sound Practices. Government of Canada. Retrieved July 2020, from <https://www.osfi-bsif.gc.ca/Eng/fi-if/rg-ro/gdn-ort/gl-ld/Pages/b9.aspx>

Pacific Climate Impacts Consortium (2020). Plan2Adapt. University of Victoria. Retrieved September 2020, from <https://www2.gov.bc.ca/gov/content/environment/climate-change/adaptation/impacts>

People of the State of New York v. Exxon Mobil Corporation, 65 Misc. 3d 1233(A), 2019 N.Y. Misc. LEXIS 6544, 2019 NY Slip Op 51990(U), 49 ELR 20199, 2019 WL 6795771 (Supreme Court of the State of New York).

Poggio, M. (2019, January 22). Next Climate Liability Suits Vs. Big Oil Could Come from Western Canada. Climate Liability News. Retrieved July 2020, from <https://www.climateliabilitynews.org/2019/01/22/climate-liability-western-canada-vancouver-victoria/>

Porter, K., Scawthorn, C., Huyck, C., Eguchi, R., Hu, Z., Reeder, A. and Schneider, P. (2018). Natural Hazard Mitigation Saves: 2018 Interim Report. Washington, D.C.: National Institute of Building Sciences. Retrieved July 2020, from <https://cdn.ymaws.com/www.nibs.org/resource/resmgr/mmc/NIBS_MSv2-2018_Interim-Repor.pdf>

Porter, K. and Scawthorn, C. (2020). Estimating the benefits of Climate Resilient Buildings and Core Public Infrastructure (CRBCPI). Toronto: Institute for Catastrophic Loss Reduction. Retrieved July 2020, from <https://www.iclr.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/SPA-Climate-resiliency-book.pdf>

Province of Ontario (n.d.). Ontario Green Bond Framework. Retrieved April 2020, from <https://www.ofina.on.ca/pdf/green_bond_framework.pdf>

Rabson, M. (2020, September 23). Supreme Court reserves judgment in Canada’s carbon tax cases. Retrieved September 2020, from <https://globalnews.ca/news/7353756/supreme-court-canada-carbon-tax/>

Ralph, O. (2018, September 6). Global catastrophe bond market size climbs to a record $30bn. Financial Times. Retrieved July 2020, from <https://www.ft.com/content/d62827b2-b1e0-11e8-99ca-68cf89602132>

Reference re Greenhouse Gas Pollution Pricing Act, 2019 ABCA 283, 2019 CarswellAlta 1454, [2019] A.W.L.D. 3342, [2019] A.W.L.D. 3442, 2019 D.T.C. 5101, 307 A.C.W.S. (3d) 520 (Alberta Court of Appeal).

Reference re Greenhouse Gas Pollution Pricing Act, 2019 ONCA 544, 2019 CarswellOnt 10495, 2019 D.T.C. 5090, 146 O.R. (3d) 65, 29 C.E.L.R. (4th) 113, 306 A.C.W.S. (3d) 514, 436 D.L.R. (4th) 1 (Ontario Court of Appeal).

Reference re Greenhouse Gas Pollution Pricing Act, 2019 SKCA 40, 2019 CarswellSask 204, [2019] 9 W.W.R. 377, 2019 D.T.C. 5055, 304 A.C.W.S. (3d) 531, 435 C.R.R. (2d) 1, 440 D.L.R. (4th) 398 (Saskatchewan Court of Appeal).

Richard Lauzon c. Muncipalité Régionale du Comté (MRC) de Deux-Montagnes, Ville de Sainte-Marthe-sur-le-lac, Procureur Général du Québec, 2019 QCCS 4650, EYB 2019-326677 (C.S. Qué.).

Riordan, R. (2020, March). Transition Bonds. Retrieved July 2020, from <https://smith.queensu.ca/centres/isf/resources/primer-series/transition-bonds.php>

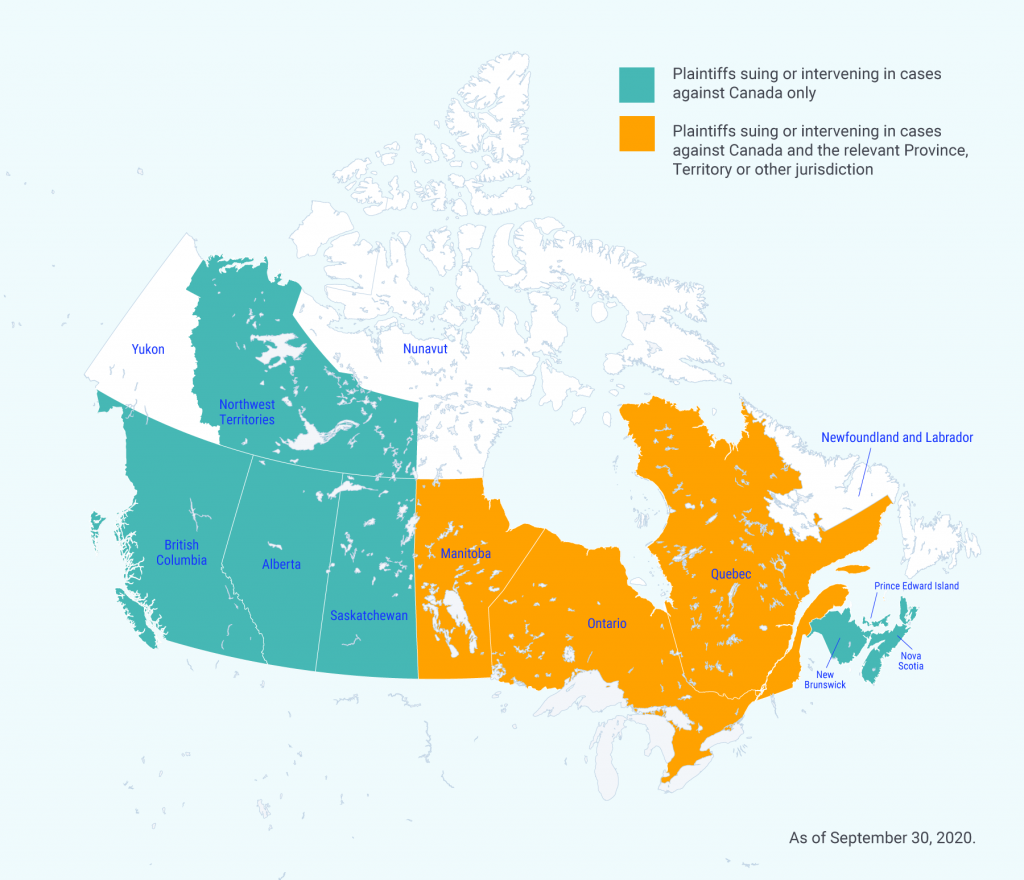

Sabin Center for Climate Change Law (2020). Climate Change Litigation Databases. Columbia University, Columbia Law School and Columbia University Earth Institute. Retrieved September 2020 from <http://climatecasechart.com/>

Sarra, J. and Williams, C. (2018). Directors’ Liability and Climate Risk: Canada – Country Paper. Smith School of Enterprise and the Environment, Commonwealth Climate and Law Initiative. Oxford: University of Oxford. Retrieved July 2020, from <https://ccli.ouce.ox.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/CCLI-Canada-Paper-Final.pdf>

Securities Act, R.S.O. 1990, c.S5 (1990).

Setzer, J. and Vanhala, L. (2019). Climate change litigation: A review of research on courts and litigants in climate governance. WIREs Climate Change, 10(3). Retrieved March 2021, from <https://doi.org/10.1002/wcc.580>

Sierra Club Canada Foundation v. Canada (Environment and Climate Change Canada), 2020 CarswellNat 2170, 2020 CarswellNat 2171, 2020 FC 663, 2020 CF 663, 320 A.C.W.S. (3d) 58 (Federal Court).

Shrubsole, D., Brooks, G., Halliday, R., Emdad, H., Kumar, A., Lacroix, J. and Simonovic, S. P. (2003). An Assessment of Flood Risk Management in Canada. Toronto: Institute for Catastrophic Loss Reduction. Retrieved July 2020, from <https://www.iclr.org/wp-content/uploads/PDFS/an-assessment-of-flood-risk-management-in-canada.pdf>

Standards Council of Canada (2019). Sustainable Finance-Defining Green Taxonomy for Canada. Retrieved July 2020, from <https://www.scc.ca/en/standards/notices-of-intent/csa/sustainable-finance-defining-green-taxonomy-for-canada>

Sun Life (2019a). Sustainability Bond Framework. Retrieved July 2020, from <https://cdn.sunlife.com/static/Global/Investors/Investor%20briefcase/Sun%20Life%20Sustainability%20Bond%20Framework_March%202019.pdf>

Sun Life (2019b). Sun Life announces inaugural Sustainability Bond Offering. Retrieved July 2020, from <https://www.sunlife.com/Global/Investors/Financial+news/Announcement/Sun+Life+announces+inaugural+Sustainability+Bond+Offering?vgnLocale=en_CA&id=123278>

Sustainability Accounting Standards Board (2018). Retrieved April 2020, from <https://www.sasb.org/>

Sustainable Development Goals (2015). Transforming our world: the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. Retrieved July 2020, from <https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/post2015/transformingourworld>

Syncrude Canada Ltd. v. Attorney General of Canada, 2016 FCA 160, 2016 CarswellNat 1870, 100 C.E.L.R. (3d) 179, 266 A.C.W.S. (3d) 624, 398 D.L.R. (4th) 91, 483 N.R. 252 (Federal Court of Appeal).

Takatsuki, Y. and Foll, J. (2019). Financing brown to green: Guidelines for Transition Bonds. AXA Investment Managers. Retrieved July 2020, from <https://realassets.axa-im.com/content/-/asset_publisher/x7LvZDsY05WX/content/financing-brown-to-green-guidelines-for-transition-bonds/23818>

TCFD [Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures] (2017). Final Report: Recommendations of the Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures. Retrieved July 2020, from <https://www.fsb-tcfd.org/publications/final-recommendations-report/>

TCFD [Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures] (2019). TCFD: 2019 Status Report (June 2019). Retrieved July 2020, from <https://www.fsb-tcfd.org/publications/tcfd-2019-status-report/>

The Atmospheric Fund (2020). TAF Programs. Retrieved July 2020, from <https://taf.ca/programs/>

The Canadian Council for Public-Private Partnerships (n.d.). SP3CTRUM. Retrieved February 2020, from <http://www.p3spectrum.ca/>

The Geneva Association (2018a). Climate Change and the Insurance Industry: Taking Action as Risk Managers and Investors. Zurich: The Geneva Association. Retrieved July 2020, from <https://www.genevaassociation.org/research-topics/extreme-events-and-climate-risk/climate-change-and-insurance-industry-taking-action>

The Geneva Association (2018b). Managing Physical Climate Risk: Leveraging Innovations in Catastrophe Risk Modelling. Zurich: The Geneva Association. Retrieved July 2020, from https://www.genevaassociation.org/research-topics/extreme-events-and-climate-risk/managing-physical-climate-risk%E2%80%94leveraging>

The Geneva Association (2019). Investing in climate-resilient decarbonised infrastructure to meet socio-economic and climate change goals. Zurich: The Geneva Association. Retrieved July 2020, from <https://www.genevaassociation.org/sites/default/files/research-topics-document-type/pdf_public/infrastructure_investment_gap_4-pager_091219.pdf>

The Geneva Association (2020). Flood Resilience in a Changing Climate: A Holistic Multi-Stakeholder Forward-Looking Approach to Flood Risk Management.

The Municipal Act, S.O. 2001 c.25 (2001).

Tsleil-Waututh Nation v. Attorney General of Canada, 2018 CAF 153, 2018 FCA 153, 2018 CarswellNat 4685, 2018 CarswellNat 4686, [2018] 3 C.N.L.R. 205, [2018] F.C.J. No. 876, 21 C.E.L.R. (4th) 1, 295 A.C.W.S. (3d) 775, 45 Admin. L.R. (6th) 1, EYB 2018-301376 (Federal Court of Appeal).

Turp v. Minister of Justice and Attorney General of Canada, 2012 FC 893, 2012 CF 893, 2012 CarswellNat 2932, 2012 CarswellNat 2933, 2012 FC 893, 2012 CF 893, [2012] A.C.F. No. 944, [2012] F.C.J. No. 944, 219 A.C.W.S. (3d) 730, 415 F.T.R. 192 (Eng.), 72 C.E.L.R. (3d) 36 (Federal Court).

UNEP Finance Initiative (2019). Changing Course: A comprehensive investor guide to scenario-based methods for climate risk assessment, in response to the TCFD. Retrieved July 2020, from <http://www.unepfi.org/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/TCFD-Changing-Course-Oct-19.pdf>

United Nations (2015). Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction 2015‒2030. Retrieved July 2020, from <https://www.unisdr.org/we/inform/publications/43291>

United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (2015). The Paris Agreement. Retrieved July 2020, from <https://unfccc.int/files/essential_background/convention/application/pdf/english_paris_agreement.pdf>

Urgenda Foundation v. the State of the Netherlands (2019). 19/00135 (Supreme Court of the Netherlands), aff’g (2018), 200.178.245/0 (Hague Court of Appeal), aff’g (2015), C/09/456689 / HA ZA 13-1396 (Hague District Court). Retrieved July 2020, from <http://climatecasechart.com/non-us-case/urgenda-foundation-v-kingdom-of-the-netherlands>

Vaijhala, S. and Rhodes, J. (2018). Resilience Bonds: a business-model for resilient infrastructure. Veolia Institute. Retrieved July 2020, from <https://www.institut.veolia.org/sites/g/files/dvc2551/files/document/2018/12/03-02_Resilience_Bonds_a_business-model_for_resilient_infrastructure.pdf>

von Peter, G., von Dahlen, S. and Saxena, S. C. (2013). Unmitigated Disasters? New Evidence on the Macroeconomic Cost of Natural Catastrophes. BIS Working Paper No. 394. Retrieved July 2020, from <https://ssrn.com/abstract=2195975>

Voters Taking Action on Climate Change v. Energy and Mines of British Columbia, 2015 BCSC 471, 2015 CarswellBC 805, [2015] B.C.W.L.D. 3277, [2015] B.C.W.L.D. 3315, [2015] B.C.W.L.D. 3461, 252 A.C.W.S. (3d) 352, 94 C.E.L.R. (3d) 35 (British Columbia Supreme Court).

Williams, C. and Routliff, J. (2017). Disclosure of Information Concerning Climate Change: Liability Risks and Opportunities. Smith School of Enterprise and the Environment, Commonwealth Climate and Law Initiative. Oxford: University of Oxford. Retrieved July 2020, from <https://ccli.ouce.ox.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/Cynthia-Williams_Disclosure-of-Information-Concerning-Climate-Change.pdf>

Wolfrom, L. and Yokoi-Arai, M. (2016). Financial instruments for managing disaster risks related to climate change. OECD Journal: Financial Market Trends, 25–47. Retrieved July 2020, from <https://doi.org/10.1787/fmt-2015-5jrqdkpxk5d5>

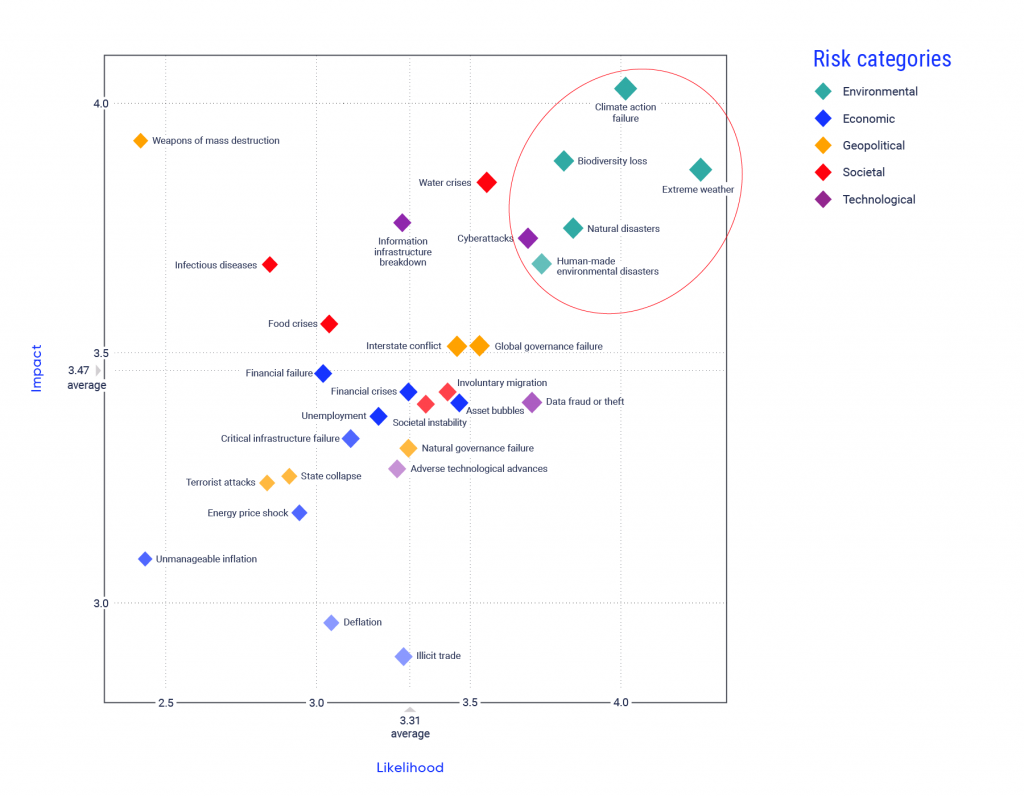

World Economic Forum (2020). The Global Risks Report 2020. Retrieved July 2020, from <https://www.weforum.org/reports/the-global-risks-report-2020>

Yohe, G. and Strzepek, K. (2007). Adaptation and mitigation as complementary tools for reducing the risk of climate impacts. Mitigation and Adaptation Strategies for Global Change, 12(5), 727‒739. Retrieved July 2020, from <https://doi.org/10.1007/s11027-007-9096-3>

York County v. Rambo, 3:19-cv-00994 (n.d.). Retrieved July 2020, from <http://climatecasechart.com/case/york-county-v-rambo/>

Zhang, X., Flato, G., Kirchmeier-Young, M., Vincent, L., Wan, H., Wang, X. and Kharin, V. (2019). Changes in Temperature and Precipitation across Canada. Chapter 4 in Canada’s Changing Climate Report, (Eds.) E. Bush and D.S. Lemmen. Government of Canada, Ottawa, Ontario, 112–193. Retrieved February 2020, from <https://changingclimate.ca/CCCR2019/chapter/4-0/>